Spoiler warnings for the entire run of Death Note in manga and anime, the Netflix live-action adaptation, and the first two Japanese live-action movies by Nippon TV.

Content warning for extensive discussion of death and death imagery.

Death Note, written by Tsugumi Ohba and illustrated by Takeshi Obata, is one of the most iconic manga ever created and a regular feature on many people’s Top 10 Anime/Manga Of All Time lists. I don’t just mean iconic in terms of fame. The iconography of the series is extremely strong, providing a ton of instantly recognizable quotes and images that have made it a marketer’s dream since the manga debuted in 2003. It’s inspired an anime, a handful of light novels and video games, TV dramas, musicals, you name it. It’s also inspired a series of extremely popular and well-received Japanese live-action movies and a Netflix adaptation that has proven unpopular among viewers and critics alike.

Part of the problem is that the manga’s most beloved characters were faithfully adapted by Nippon TV but unrecognizable on Netflix. Another part of the problem is that Nippon TV closely adapted Death Note’s complex story, with an original third act that fit seamlessly with the existing characters and their motivations, while Netflix opted for an entirely original story that didn’t stand up to the intricacies of the manga. But at least both adaptations are immediately recognizable as Death Note, right? Well…

As in the previous articles, the original manga and anime will be referred to as Death Note. The Nippon TV adaptation will be referred to as Death Nippon, and only the first movie in the series will be discussed. The Netflix adaptation will be referred to as Death Netflix. The killing journal that the series is named after will be referred to as the Notebook.

Imagery

I wasn’t a teenage girl in Japan in 2003, but luckily a friend of mine was, and she wants you all to know something important about goth in Japan: it’s a lot of fun.

It’s often unpopular among traditional parents, but what’s the point of a youth fashion culture that parents like? Goth in Japan is a form of expression that is about having fun dressing up in awesome-looking outfits and hanging out with other people doing the same thing while listening to cool foreign music. Goths in the west are not completely joyless people, obviously, but that brand of goth is based very heavily in Victorian mourning; western goth subculture is deliberately dripping with death imagery and sorrow.

It probably goes without saying, but I’ll say it anyway just in case, that western and Japanese funerals are wildly different affairs and there is very little overlap in dress or iconography. While Japanese goths are aware that goth has a lot to do with western death and mourning, it just doesn’t immediately evoke a feeling of mortality for them the way it would for a westerner. Goth in the west is a subculture and a lifestyle; goth in Japan is pretty much pure #aesthetic. All that black lace and eyeliner and all those crucifixes just look cool, okay? This is also why goth, in Japan, crosses over with a lot of other fashion styles, especially Lolita fashions (speaking of western ideas that are stripped entirely of their context when transformed into Japanese fashion…). Such things happens when fashions move outside of the culture that they originated in.

This is important to understand in regards to Death Note because the series is, understandably enough, absolutely covered in death imagery that’s very familiar to western audiences, but doesn’t mean the same thing in Japan. It’s about looking cool, not looking sinister.

The character of Misa Amane is probably the best example of goth in Japan, especially in the early noughties. She’s an idol—a girl who makes her living being cute, peppy, and friendly in as many forms of media as she can lay hands on—and she does it dressed in goth. Almost all of her outfits in the first half of the manga are heavy on the black lace and crucifixes. In Death Nippon, she can be seen hosting a cutesy cooking show where she talks about baking sweets while wearing black studded platform shoes and a black tank top that seems to be made of fishnet, black lace, and silver sequins in the shape of a skull-and-crossbones. To Japanese audiences, there is nothing contradictory about the outfit and a sweet, bubbly starlet baking desserts.

Again, let me stress: goth in Japan, and in Death Note, is about looking cool, not looking scary or sinister. The goth imagery is a bit toned down in Death Nippon, largely due to the differences between presenting a story on the page and in live-action. The most goth parts of the movie are the most recognizable pieces of iconography–the Notebook itself and the occasional appearance of onscreen text from the Rules, the website dedicated to Kira, L’s insignia and Ryuk. These are the pieces that adorn pretty much every necklace, bag, t-shirt, wallet, poster, and what have you that you can buy.

This kind of merch actually creates an impression of Death Note being more goth than it really is. Misa and the shinigami are the only characters with distinctively goth aesthetics; Light consistently dresses as proper as proper can be, aside from the occasional hoodie, as do the police officers who make up the bulk of the supporting cast. L and all of his successors are primarily associated with light-colored or even white looks, as well as toys and sweets. A running theme of Death Note was that you couldn’t tell who was dangerous just from how they looked. The four official Kiras were a straight-A student and son of a cop, a cheerful pop idol, a successful business executive, and a respectable criminal prosecutor. Death Nippon, in step with the manga, really isn’t all that goth aside from the most famous icons noted above, especially due to the lack of Misa or any shinigami except Ryuk.

There is some cheese present in that the art museum that features twice is hosting an exhibition of death art, but it manages to be just subtle enough to avoid being a stinker. Nobody ever stops to stare at the paintings while monologuing about the meaning of death. None of the artwork is ominously foregrounded during a montage or while people are talking. The most ominous thing that happens during Light’s first visit is Shiori mentioning that she’s too shy to kiss him in public unless it’s their last kiss. The second museum trip is a fraught, tense scene that ends with two women dead, but the whole time the death art in the background is just that…background. Thematically appropriate set dressing that’s never shoved down the audience’s throat. What matters, in both scenes, are the actions of the characters inside of the museum, not the art and aesthetic.

From the moment that a dramatic rainstorm kicked up when the Notebook fell down in front of Light, I knew that Death Netflix was going to be very different.

One of the weird things about Death Netflix’s visuals is that they aren’t goth, they’re emo, which is less about a specific aesthetic than it is about bucking certain social conventions. Visually it’s literally a lot darker, with a lot of scenes happening at night or in poorly-lit rooms. Mia dresses in dark colours and behaves with a complete lack of interest in anything not death-related. Light also dresses darkly save for his frosted tips, which, we can all agree that those were a terrible idea, right? I’m no hairstylist, but I can’t think of anything that makes frosted tips a better idea than a blond dye-job or wig save for the part where they contribute to Light’s appearance as a social outcast. Light and Mia aren’t the dangerous criminals hiding within respectable and popular society, they visibly reject and are rejected by society and that’s visually tied to their personal fixations on death.

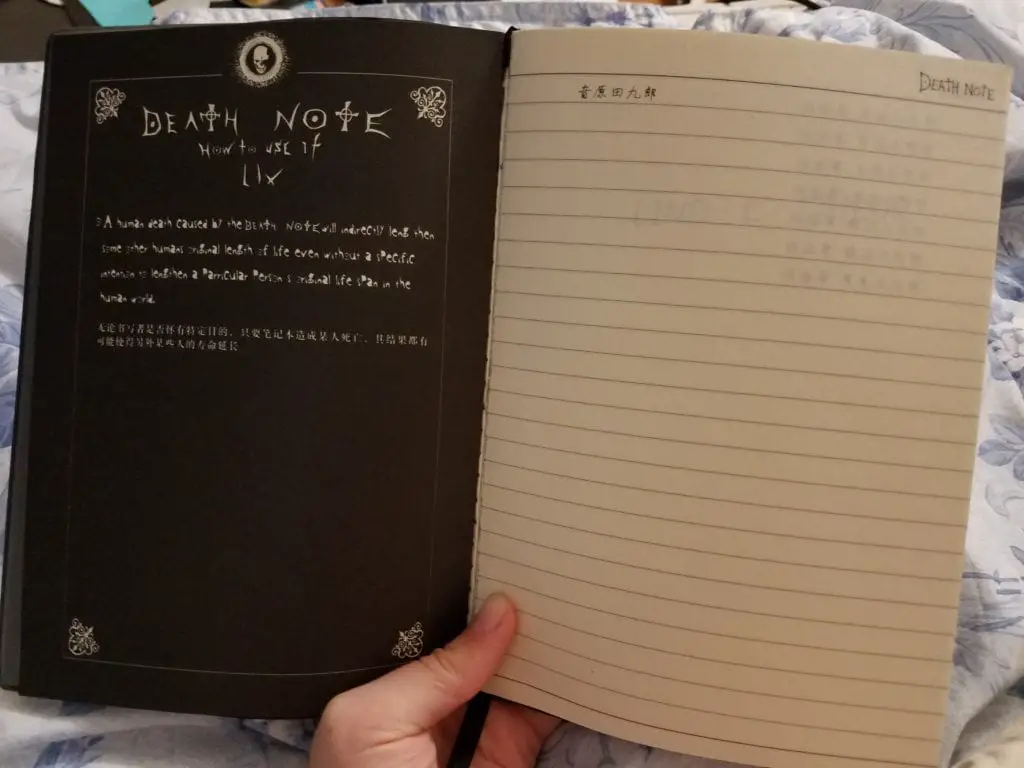

Part of this shift in aesthetic has also resulted in the most iconic imagery in the series being altered or outright dropped. This is especially odd since seeing a Death Note t-shirt in Hot Topic seems to be where Adam Wingard got the idea for the adaptation. Most immediately obvious is that the Notebook itself looks very different to how it looks in literally everything else ever. That includes the actual physical Notebooks that you can buy, complete with most of the names that Light writes in the manga already written in to the first few pages after the dozens of pages of Rules.

The Notebook in Death Netflix, however, has four eyes on the corners of the cover rather than being blank black save for the title. The Rules inside also look completely different. They’re written in black ink on brownish parchment rather than white ink on odd black paper, and utilize a generic-gothic font rather than the unique, blotchy font of Death Note that, among other things, often replaced the letter “t” with a crucifix. The original font also dotted the inside of any vaguely circular letters (most notably “O”s and “D”s), which created a much more subtle and unsettling effect of eyes watching than just plastering the cover with random eyes did.

#ForTheAesthetic is, of course, a part of the design of Death Note, but that went hand-in-hand with appearance having little to do with nature. Making the Notebook more visually sinister is a pretty obvious red flag that Death Netflix wants you to quite literally judge a book by its cover. It also fails, because personally, I think those eyes just make it damn cheesy, not scary.

Ryuk’s appearance is actually largely faithful, aside from his shoulders being changed from slightly feathered and expanding into wings to porcupine-like quills. Of course, Ryuk already looked plenty sinister… despite being extremely uninterested in actually killing anybody and generally being the manga’s comic relief character until literally the last chapter. Again, a case of appearance not representing character was changed by keeping Ryuk looking as sinister as he now behaves. Weirdly, his apple-eating habits were also changed. In Death Netflix, he regularly announces his presence and generally dicks with Light by throwing apple cores at him rather than ever eating an apple whole as he does in the manga, entirely For The Drama™.

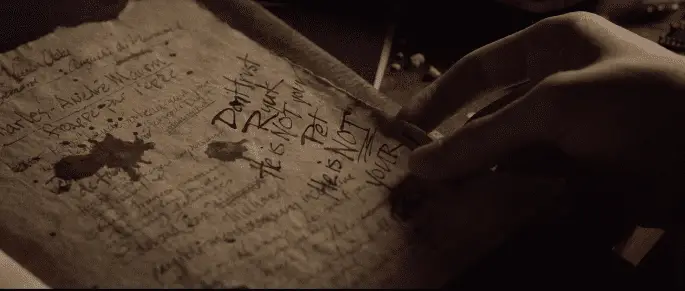

I think it’s worth repeating that while the goth aesthetic in Death Note is shallow, the series itself is not. Light Yagami is an undeniable drama queen, but that tendency towards drama and hubris is specifically the character flaw that destroys him, not just pure aesthetic. Nevertheless, needless drama runs throughout Death Netflix, and nowhere is that more obvious than when Light finds a warning scrawled in the Notebook: “Don’t trust Ryuk. He is not your pet. He is NOT your friend.” Next to a couple of splotches of blood, for good measure.

Storywise, this warning has no function but to make Light (and the audience) suspect that Ryuk killed the FBI agents, which he didn’t. Between Ryuk’s jumpscare introduction, his repeated threats to kill Light if he gets boring, and the fact that Light and Ryuk never interact enough to develop the banter that they have in the manga and Death Nippon, this note really isn’t telling us anything that wasn’t immediately obvious about the shinigami. And it also functions to contradict one of the key attempts at actual drama in Death Netflix: Light confronting Ryuk about killing the FBI agents.

The cinematography and music for this scene are pure drama, dressing the scene up like a major moment, but how it plays out is just odd. Why does Ryuk never just say that he didn’t kill the FBI agents? Because withholding that information makes him look dramatic and sinister. Why is he sitting at Light’s kitchen table eating apples in the dark and tossing the cores at Light’s feet in the first place? Because it looks dramatic and cool, dammit. Why does he tell Light “my name has four letters. The most anybody’s ever gotten was two” when we’ve already seen otherwise? Because it’s an awesome line, and fuck the idea of making any sense.

I would like to say that I am not against the Rule of Cool, but I don’t think you should hang any of your story on it when you are, from the off, behaving like your story is deep and serious. There was at least one non-contradictory dramatic option available: Ryuk could have challenged Light to write his name in the Notebook and then simply stood and cackled while it did nothing. Ryuk’s name is written in the Notebook already and it didn’t kill him, and while this rule is never quoted in the movie it is canon to Death Note that Notebooks cannot kill shinigami. Ryuk could have mocked Light for his inability to harm the shinigami, but instead opted to be actively threatening.

I feel like it’s also worth mentioning that at the end of Death Note, when Light demanded that Ryuk kill the agents and police who’d cornered him and Ryuk instead killed Light, this betrayal was a major plot twist. The entertaining way that Ryuk and his interactions with Light were written allowed the readers to forget that Ryuk was not Light’s friend and never actually cared how the whole thing played out, so long as it was fun to watch. Wanting to put your own distinct aesthetic onto an adaptation is not a sin, but the #ForTheAesthetic shouldn’t devour the characters. And it is weird to adapt something with such distinct icons and change nearly every one of them.

L’s gothic, heavily stylized “L” insignia is also absent, but so is most of his actual role in the story, so.

How do they compare?

I don’t think there’s any other way to put this than that Death Nippon looks like Death Note and Death Netflix doesn’t. Death Netflix is an extremely odd case of an adaptation that has apparently only taken in its source’s aesthetic and nothing else, and at the same time completely failed to understand that aesthetic. Hot Topic Emo is not a cultural equivalent to Harajuku Goth. The former sells a lifestyle based on not fitting in, the latter entertainment based on standing out, and those are just not the same thing.

Not to keep beating a dead horse (though the flayed and cleaned skeleton would make a pretty sick garden decoration), but a very integral part of Death Note was that appearance did not show morality. The goth aesthetics were all about looking cool, not scary, and the scariest characters in the series didn’t look frightening at all. I’m a bit baffled then on how Wingard apparently looked no further than the icons when picking a series to adapt and then even disregarded them.

One thing that both adaptations seem to have in sync, at least, is weird musical choices. “I Don’t Wanna Live Without Your Love” gave a downright surreal tone to Mia’s death scene in Death Netflix. Then again, Death Nippon left off a very serious ending by going into “Californication” for the credits. I suppose Death Nippon has the excuse of having picked a cool-sounding foreign song with no expectation of the audience understanding the lyrics, just the intense riffs. And at least they saved that tonal weirdness for the credits instead of peppering the whole movie with it as Death Netflix did.

Script

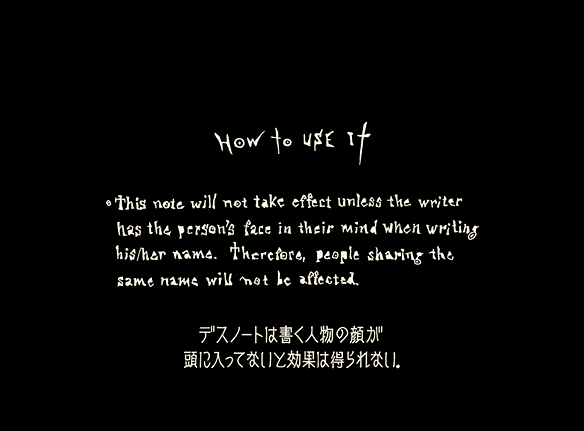

When talking about the way the script for these movies was written, there are specific quotes I want to look at. First, the Rules of the Notebook. They’re inarguably the most important piece of lore in the series. They regularly got whole pages to themselves in the manga. They were written out in their entirety in the supplemental materials, the anime opened and closed ad breaks by displaying relevant Rules, and the intricacies of the plot all hung on the Rules and the loopholes in them that Light and other characters discovered and manipulated. And yes, Rules should be capitalized every time. They’re that important.

A grand total of 126 Rules are listed in How To Read, though only about a third of those actually came into play in the manga. Obviously, both adaptations significantly reduced the number of Rules that were quoted and explained, depending on what was relevant to their respective stories.

In Death Nippon, six specific Rules are explained. The iconic “the human whose name is written in this note shall die” is read aloud by Light when he first finds the book and the Rules page is shown onscreen. Ryuk later explains that a human who owns a Notebook can trade half their lifespan for the Shinigami Eyes, the power to see other humans’ true names and lifespans. Four other Rules are shown onscreen as they become relevant to the story, written in English and Japanese.

Every single Rule quoted is lifted verbatim from the manga, right down to the situations in which these Rules are quoted. No new Rules are quoted in the entirely original third act, but Light manipulates the already-revealed Rules in a new and interesting way, which is fitting to how he constantly manipulates the Rules of the Notebook in Death Note. This also means that Death Nippon never actually changes the Rules of the Notebook, yet still manages to use them creatively, which fits the source very well, rather than, say, coming off as manipulating a quote out of context.

Death Netflix also shows us five Rules onscreen in addition to quoting a couple aloud. Rule 95, “anyone may write names in the note but only the keeper may possess the note for more than 7 days.” This is a Rule entirely original to Death Netflix, as is the unnumbered but oft-quoted Rule that “Burning the page on which someone’s name is written, prior to their death, means their death can be avoided. However, this can only be done once.” Ryuk also mentions that only the Notebook’s Keeper can see him, another Rule original to Death Netflix. In the manga anybody who touched the Notebook could see its shinigami.

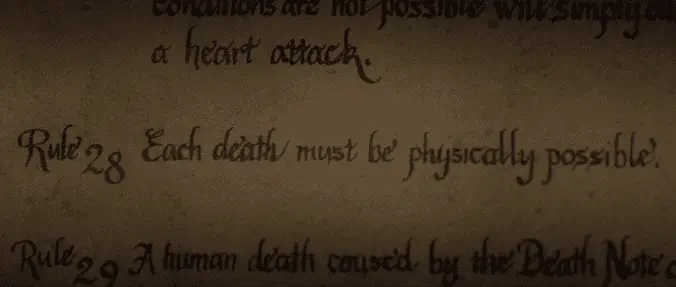

Of the five rules we are shown onscreen, all but Rule 1 have had their wording and/or function changed. Probably most telling is that the timespans for several rules have been changed, such as the 23 Day Rule, which explained that a victim could only be controlled for up to 23 days prior to their death. In Death Netflix, this has been reduced to a mere 48 hours. Death Note stated that a Notebook’s owner would have to not touch it for 490 days to lose possession of it, while in Death Netflix that’s been changed to a seven days. All of these Rules have been crunched down to allow a series of tense races against time, presumably because that’s better for action sequences.

However, the changes also mean that Light and Mia both embark on plans that are treated by the narrative as if they are clever and creative but actually involve nothing more than just following the Rules of the Notebook present in the source material but not shown onscreen. Light Yagami of Death Note started abusing loopholes and creative uses of the Notebook very early on. The busjacking, for example, utilized the writing of a mundane note on a piece of Notebook paper led and tricking the busjacker into picking it up so he could see and be terrified by Ryuk. None of that is present in Death Netflix until Light Turner’s final gambit, where he uses epithets to manipulate Mia’s death into burning his page of the Notebook. This is a very Light Yagami thing to do, but unfortunately, it might just be too little, too late.

A small but somewhat jarring alteration is Rule 28’s wording being altered. It’s not so much the simplification of the wording that’s odd, but the jaunty little exclamation mark at the end is weird as all hell. It’s a stark contrast to the solemn, litigious way that most of the Rules are generally written, and feels a little like it’s undermining the fact that these are Rules of murder. It stinks of “lol quirky”. It’s a little thing, one of those things that could probably be brushed past without concern in a better movie, but in this case comes off as yet another indicator that nobody on this project, from the writers to whoever prepared the prop, actually understands or cares about Death Note.

Death Nippon lifted a great deal of its script directly from the pages of the manga, while Death Netflix’s was largely original, but of particular note is how each adaptation uses Ryuk’s catchphrase “humans are so… interesting!”. Death Nippon brings it up on several occasions when Ryuk is watching Light pull off some particularly clever shit with the power of the Notebook, but also when he witnesses Light the mass-murderer sharing tender moments with his girlfriend. The contrast of situations highlights the contrasting character traits in Light and just how fascinating the otherworldly shinigami finds them to be.

This catchphrase appears only once in Death Netflix, and it’s the final line of the film. Ryuk cackles it out after hearing Light confess how he arranged his girlfriend’s death and exonerated himself using the Notebook. It’s somewhat appropriate, since this plan is the first time that Light actually is interesting. But the fact that it’s the final line before the credits also feels just a little like using a famous line for your final impression of the movie in order to remind you that, oh yeah, this was based off of Death Note.

It also gives the final scene a very different tone to the final scenes of Death Nippon. One of the last things that Ryuk says to Light Yagami, after hearing how he killed his girlfriend, is a solemn “you know what, Light? You’re worse than any shinigami.” This paraphrases not Ryuk but Rem, a shinigami in Death Note whose death Light causes through some truly merciless emotional manipulation. Rem’s dying words were, “But Light Yagami… to kill even a shinigami… he’s surpassed the shinigami”.

The use of this line in Death Nippon, combined with the somber music and colorless background, sells what Light just did as incredibly evil. Ryuk cackling in a weirdly colorful hospital room sells Light’s betrayal-and-murder plan as cool, despite his conversation with his dad about being evil. Death Nippon isn’t exactly a case of “show, don’t tell” as Ryuk straight up calls Light worse than a death god, but Death Netflix does a good job of displaying how the tell can really be undermined by the show if they’re in conflict.

How do they compare?

It’s actually very difficult to compare the scripting of Death Nippon and Death Netflix, the former being so faithful to the source and the latter being so different. But how they handle the quotes they do have in common is very telling. Death Nippon transplanted Rem’s final words to Ryuk while remaining sensitive to how serious they were, while Death Netflix employs Ryuk’s catchphrase without actually using it as a catchphrase in the movie. This means that either a) the movie ends on a note of approval for Light’s actions or b) it ends on a famous line of the sake of reaching for audience approval points.

Using famous lines from the source without understanding their context when adapting it is… well, it’s bad. It screams a lack of understanding as well as a lack of respect for the source material, and that’s going to rub any fan the wrong way. It’s a scrape for approval that might appease less critical watchers, but is painfully transparent to more dedicated fans.

And when you’re adapting a property with a huge built-in fanbase, why throw that away by wildly misquoting and rewriting the central lore of the entire series? The Rules of the Notebook are possibly the easiest thing in the world to quote; they’re written down in a handy little list that comes with all sorts of merch, and there’s over a hundred of the bastards for you to pick and choose from. But they’re all designed to encourage planning and manipulation, not desperate chase scenes, and Wingard doesn’t seem to believe that audiences are interested in intellectual feats until they’ve seen somebody chase somebody else with a gun.

In Conclusion (for the last time)

Look, you came into these articles knowing that Death Netflix was bad. Everybody knows by now that Death Netflix was bad. On every possible level, it’s disrespectful to its source material and the fans of it. Taken as an original piece of work with no connection to Death Note, it’s deeply uninteresting. But this can’t be brushed off as the inevitable result of cramming a widely beloved and famously complicated manga into a movie, because better adaptations already exist.

The Japanese adaptation isn’t inherently better because it’s Japanese or because it has a Japanese cast. It’s better because it understands what Death Note is—what it’s about and what the fans love about it—and made an adaptation designed for those fans. No doubt it’s pandering, it’s absolutely pandering, you cannot pander harder to the Death Note fanbase than by giving Naomi Misora more screentime. But let’s agree that when it comes to adapting a popular piece of work, there’s a big difference between pandering to that work’s existing fanbase and pandering to a hypothetical wider audience of simplistic thrill-junkies.

It’s not even a cultural difference, because it’s also the difference between Wonder Woman‘s success versus Batman v Superman being a shitshow. It’s about understanding why a story was so popular in the first place and working to respect that popularity. Death Nippon took plenty of original turns of its own, such as transplanting the setting and fabricating a whole third act. These choices worked because they fit the already existing story, themes and characters. Death Netflix’s original work didn’t gel with Death Note, and barely even gelled with Death Netflix, because the pursuit of Drama™ riddled the story with plot holes and inconsistent characterization.

While Death Netflix’s problems are not solely a result of its cultural transplant, the way it was recreated was definitely a textbook case of bad Americanization. Moral complexity was replaced by a more straightforward protagonist/antagonist divide, intellectual fights were replaced by physical ones, and time was taken away from building an emotional center to be given to elaborate, gory deaths. It’s not a good way to adapt movies. It’s not a good way to make movies.

And, though I’ve avoided discussing it too much because I feel like it’s not my discussion to run, Americanizing a movie does not mean making it white. Given the way his character was handled, casting L as black is not a get-out-of-criticism-free card for movie otherwise filled with white faces; especially not for a movie set in a melting pot of a country with tens of millions of Asian-Americans, including at least 1.3 million Japanese-Americans. And there were so many ways that L’s casting could have been used to examine the intersection of race and injustice that exists in America in a way that it doesn’t in Japan, and they just… didn’t.

Perhaps that’s what’s most insulting is that even in going with an original take, Wingard had vast possibilities in front of him and chose possibly the blandest and least interesting way to tell this story. Of course, a talented person with the ability to do great things in the world committing atrocities instead is the story of Death Note…