Spoiler warnings for the entire run of Death Note in manga and anime, the Netflix live-action adaptation, and the first two Japanese live-action movies by Nippon TV.

Content warning for images featuring blood and extensive discussion of death, murder, and suicide.

Netflix’s adaptation of Death Note is at best, not the least popular western adaptation of a popular Japanese anime ever made. Part of the problem is the whitewashing, which is a big damn problem all on its own. Part of the problem is the fact that almost none of the iconic characters who made the original manga and anime so popular have been translated with any degree of faithfulness. And part of the problem is that, along with essentially original characters, this adaptation is at least half-original plotline that has not landed particularly well.

It’s a basic fact of adaptation that adapting a beloved piece of media is walking a fine line. Change is inevitable, especially when compressing a plot as intricate as Death Note‘s into less than two hours of runtime. But streamlining a story is one thing; when replacing it with something else, it had better be good.

The 2006 live-action adaptation of Death Note, created in Japan and produced by Nippon TV, invented both a significant subplot of the first act and the plot as an entirety third act. Yet it remains a critical and popular darling to this day. So where did Nippon TV go right where Netflix went wrong?

For the sake of clarity, as in part 1, Death Note will refer to the original manga and the anime which was, save for a couple of scenes, completely faithful. Death Netflix will refer to the 2017 western adaptation on Netflix. Death Nippon will refer to the 2006 Japanese adaptation from Nippon TV. The eponymous slaughter jotter will be referred to, in all versions, as the Notebook.

Story

Death Netflix

Several of the early story beats in Death Netflix are definitely based on Death Note. Light finds the Notebook on the ground at his school, and at one point he tests its power by killing a man who is holding people hostage live on the news. L takes an interest in the serial killer Kira and decides to work with Light’s father, James Turner, on the Kira Task Force to catch him, challenging Kira directly over television. These are all aspects of the plot in Death Note, but even these are significantly altered, and the bulk of the story is entirely new.

The first act consists of Light Turner going from a nobody who gets beaten up by a bully to being in a relationship with Mia and creating the character of Kira. After finding the Notebook on the ground while doing other students’ homework for money, he jumps into a fight with a bully to protect a girl in his class with whom he’s been exchanging looks. His attempt to out-talk the bully does not end well, and in addition to getting beaten up, he gets detention for all of the other students’ homework in his bag when a teacher finds him while the bully gets off scott-free. Both of these things frustrate him no end with his teachers’ lack of perspective or interest in the school’s social problems.

During detention, he investigates the book that he found and scoffs at the rules written inside claiming that the book can kill. Until he is confronted by a creature who tells him that the book is for real and prompts him to test it on his bully. Light writes that the bully dies by decapitation, setting in motion a chain of events that leads to the bully being gorily headless in under a minute, convincing Light that the book is for real.

After arriving home and fighting with his father over the issue of his detention and the bullying at his school, Light storms up to his room and uses the Notebook to kill the man who killed his mother in a hit-and-run. He also discovers Ryuk’s name thanks to a note left by a previous owner of the Notebook. Then, Ryuk himself appears to explain some of the rules of the Notebook.

The next day, Light studies the Notebook at school and catches the attention of Mia Sutton, the classmate he’s been making eyes at. She makes awkward conversation by asking morbid questions about the bully’s death and Light’s book. Light decides to show off its power to Mia. He first lets her read it and then, on discovering that she can’t see Ryuk (a notable departure from the manga, where being able to see Shinigami after touching the Notebook was a key plot point on a regular basis), tunes in to a live news broadcast of a hostage situation. He kills the hostage-taker in a convoluted way to prove the Notebook’s power to Mia. Luckily for Light, Mia (who he’s never had a conversation with before today) is into this and tells Light that they could use the Notebook to change the world by casually committing hundreds of murders.

Light also creates the moniker of “Kira” and spreads it by having criminals write it in blood before dying, claiming that “it means ‘Light’ in Russian and Celtic.” This is wrong because a) Kira does not mean Light in Russian and b) Celtic is not one language but a family of languages and in none of them does Kira mean Light.

In Death Note, the name is created by a Japanese fansite as a corruption of the English word “killer”, and Light Yagami himself points out that it’s somewhat cringe-y but he’s stuck with it now. Light Turner choosing the name for himself is…well, it’s cringe-y. It’s also unnecessary. With the increased power of social media today, I would completely buy it if “Kira” had been created by a bunch of teenagers who mistook it for the Japanese word for “killer” and spread the name virally. All it would take is a hashtag.

The only benefit to Light making up the name is that had he not had criminals write the name in blood, there would be no discernible way to link most of the murders Kira commits to each other. This is because, rather than default to heart attacks as in Death Note, Light commits almost all of the murders in different ways. The variety of the murders allows for elaborate, gory death sequences but not for the Kira phenomenon to be noticed naturally by the police and the populace when criminals with no heart problems drop dead of unexpected heart attacks.

The second act is ushered in with the arrival of L, who we first see examining a gory mass-murder, complete with provocatively displayed dead strippers. From this crime scene, he knows that Kira is in Seattle and makes an alliance with Light’s father, apparently the only police officer in Seattle interested in catching Kira. L calls Kira out on television, infuriating Light and Mia, but they have no way to find L’s name. This confirms L’s theory that Kira needs a name and a face to kill, as the only thing linking the victims so far is that their names and faces have been public record.

FBI agents are assigned to tail anybody connected with the case that L and James are running, which includes Light. Light responds by not using the Notebook and going on “inconspicuous” dates with Mia where they wear sunglasses at night. Mia tries to convince Light to just murder the FBI agents with the Notebook, but Light refuses. However, not long after, the FBI agents commit mass suicide and Light confronts Ryuk, whom he suspects was responsible. Ryuk neither confirms nor denies Light’s suspicions, but makes it clear that while he’s not afraid of Light, Light should be afraid of Ryuk getting bored of him.

In response to the deaths, Light’s father holds another press conference, showing his name and face as he calls Kira out. Mia tries to murder James, but Light is not on board with killing his dad and throws Mia out. He takes her back pretty much the next day, though, when she tells Light that she loves him. L confronts Light to tell him that, thanks to James not being murdered, he knows Light is Kira. Light all but confesses while trying to get L’s help, but L is uninterested in helping a mass murderer.

Light hits on a new plan to find L’s name by controlling L’s assistant Watari. He plans to avoid killing Watari by burning the page of the Notebook with Watari’s name on it, utilizing a one-off rule of the Notebook original to Death Netflix. L’s desperation to get Watari back drives him to confront Light in front of his father and then, when that reveals nothing, to have Light’s house searched, though nothing is found.

For me, the oddest part of this whole thing comes down to names. As I mentioned in part one, I question why is Watari leaves his face uncovered and uses his real name if L had already figured out that Light needs a name and a face to kill. This makes even less sense when L himself covers his face and hides his name. This massive oversight on L and Watari’s parts exists entirely so that Light can control Watari, but surely it wouldn’t have added too much to the runtime to have Light track down Watari’s name somehow? It would’ve given Light a chance to flex some intellect and wouldn’t have undercut L’s own intelligence and caution. L confronting Light face-to-face isn’t out of character when he’s confident that Light can’t kill him without a name, especially if he’s trying to frustrate Light into making a mistake, but not seeing to Watari’s protection is odd.

The third act takes place primarily over the night of Light and Mia’s school dance, a move that I can’t figure out at all. Why are high school dances such a popular set-piece in American movies? I admit, I grew up in Scotland; I can’t recall a single school dance that anybody ever went to except the Leaver’s Ball, and that one had a free bar because almost everybody was over eighteen. School dances being a valuable part of anybody’s high school experience is an alien concept to me.

Anyway, during the dance Light goes to get a report from Watari so he can burn Watari’s page and save his life. He finds that the page is gone, and Watari doesn’t manage to tell Light L’s name before he’s killed. He confronts Mia, who reveals that she removed the page and killed the FBI agents—and that she’s also written Light’s name in the Notebook. She removed Watari’s page because if Light burned it, she couldn’t burn his page and save him, which she’ll only do if he gives her the Notebook and makes her its official Keeper.

Light goes to fetch the Notebook and stops to write something that we aren’t shown. Meanwhile, L receives news of Watari’s death and goes after Light with a gun, while James, upon hearing that L is gone, sends police officers to take Light into protective custody. Light and Mia mistake the incoming sirens for police coming to arrest them and flee, planning to rendezvous on a ferris wheel that they’d been to a date on before. On the way there, Light is nearly cornered by L, but L is taken out by a random passing Kira worshipper and spends the rest of the climax unconscious. What a great and climactic rivalry that was!

Light takes the gun to force his and Mia’s way onto the ferris wheel, where they argue about using the Notebook. When the police arrive, Mia snatches the Notebook from Light and he reveals that he wrote her name so that she would die if she did that. The ferris wheel starts to collapse and Light and Mia start falling out. Light grabs both Mia and the wheel, but Mia loses her grip on Light while grabbing at the Notebook, falling to her death on the boardwalk below. Light loses his grip and falls into the river.

A couple of days later, Light awakens from a fake coma in the hospital and explains to his father how he orchestrated the whole thing. He also directed Mia’s death so that she would, as she fell, tear out the page of the Notebook with his name on it and cause it to fall into a dustbin fire on the boardwalk. Meanwhile, L goes to Mia’s house and finds a page of the Notebook with the dead FBI agents’ names on it. He picks up a pen, apparently about to write Light’s name, but the scene cuts back to the hospital with James and Light. Ryuk cackles about how interesting humans are, and…then we get credits and behind-the-scenes bloopers, which is a bit of mood whiplash to say the least.

Everything in the third act is geared towards an exciting action climax rather than an intellectual battle. Mia’s plan is pretty straightforward, and L has none at all except “chase Light with a gun.” So Light’s manipulations with the Notebook are less of a brilliant gambit and more the only actual planning anybody does that night (though the speed with which he figures out the details of the plan is impressive enough to get within a mile of Light Yagami’s brilliance). The ferris wheel is visually pretty cool, especially when it starts to collapse, and the flashbacks that go with Light’s explanation are effective for re-contextualizing what we saw the first time around.

Ultimately, though, anybody hoping for the psychological conflict of Death Note will be disappointed.

As an original story, this is not personally my cup of tea. There’s a lot of flash, from the montages to the elaborate slow-mo sequences leading up to exceptionally gory deaths to the final chase sequence. It’s a story which is more aesthetic than substance, which is fine if some splat’n’sprint is all you want from it. It’s jut not what anybody who’s watching it because they liked Death Note wants from it.

The worst, I think, are the serious tactical missteps that L, Light, and Mia make in the name of moving the plot forward in the way that Director Adam Wingard wanted rather than the plot being moved by actions that it made sense for the characters to make. There’s no given reason for Mia to have to demand that Light officially give her the Notebook. There’s no mention at any time of any rule requiring him to formally hand it over to give her any control over it, and indeed, given that she has used it several times, there’s no reason that she couldn’t have just stolen it when she took Watari’s page. The only difference that we’re shown between being the Keeper and using the Notebook is the ability to see Ryuk, and she never displays any particular interest in that.

For that matter, there’s no mention of any reason why Light couldn’t burn the page with his name on it himself. His entire plan, while apparently absolving him of being Kira by causing criminals to die while he’s in a coma, offers no explanation for him fleeing from the police at the school or threatening his way onto the ferris wheel with a stolen gun. Would these phenomenally suspicious actions be brushed off that easily? To say nothing of how he makes a full confession to his dad at the end. If this actually gets a sequel, it’s either going to require that James die before he can tell anybody or that he join the rest of the cast in departing wildly from his Death Note character basis in the name of plot.

In short, Wingard seems to have laid out the beats of an action plot he wanted to write and cool scenes he wanted to film, then moved the characters according to that plot rather than vice versa. If Americanizing movies always means making them flashier, gorier, and far more intellectually and morally simplistic, you can keep it.

Death Nippon

While many of the story beats and indeed whole scenes are lifted directly from Death Note, there’s a slight shift in the order of events. In Death Nippon, the story begins about a month after Light got the Notebook, when Kira is beginning to become a global phenomenon. The first act contains multiple flashbacks to Light’s life before finding the Notebook including the night he found the Notebook and committed his first murder, his second murder and first meeting with Ryuk, and how he developed his plan to change the world through Kira. The present-day scenes introduce us to his mother, sister, and girlfriend Shiori, an entirely original character. Most of these scenes are original to the movie due to Light being in university rather than high school, the need to establish Shiori, and the extended role of Takuo Shibuimaru.

As mentioned in part one, the Takuo Shibuimaru of Death Note was simply a random street thug who harassed a woman in front of Light after he found the Notebook and happened to be the only one who stated his full name aloud. In Death Nippon, he’s expanded into a murderer who faked an insanity plea to get off of his murder charges. Light discovers that the case was thrown out during a horrified search through the Japanese police database. The many problems that riddle the Japanese judicial system are part of the basis for Death Note; the power to walk past that mess and simply mete out justice is highly seductive and accounts for Kira’s massive public support.

While studying to be a lawyer, Ligjt realizes he’s about to make himself part of a corrupt system. He tries to confront Shibuimaru personally, but is intimidated and chased away by Shibuimaru and his friends. Light throws out his law book in a fit of rage and horror, and not long after finds a new book, one with a black cover…

Most notable, after the extra scenes where Light develops a personal hatred for Shibuimaru, is the scene where Light meets Ryuk. In Death Note, this takes place about a week after Light finds the Notebook, in which time he’s killed over a hundred people; he expected a god of some sort to turn up sooner or later to punish him, so he wanted to take out as many violent criminals as he could. Ryuk is shocked but impressed, and explains that he’s not there to punish Light. There will be no divine punishment of any sort for how Light chooses to use the Notebook aside from “the pain and fear that only a user of the Death Note will come to know.” Light takes this to mean “there are no consequences,” which is the seed of his god complex.

Light’s first meeting with Ryuk in Death Nippon is very close to this scene, but it happens only moments after Light’s second kill, that of Shibuimaru. This doesn’t change a lot about Light’s reaction—he’s frightened, expecting the Shinigami to punish him for killing a man—but it does slightly change Ryuk’s initial approach to Light, as he has no way of knowing yet how extreme Light can be. This makes the big reveal of the third act much more of a shock to Ryuk, who at this time only expresses his interest in seeing what Light will do with the power of the Notebook.

The introduction of L to the police headquarters kicks off the second act, which follows Death Note much more closely. L holds a press conference, apparently showing his face and revealing his name to be Lind L. Tailor and challenging Kira to kill him. When Light loses his temper and uses the Notebook to kill Lind L. Tailor on live television, L’s masked voice comes through, announcing that Lind L. Tailor was a convict who was promised a sizable amount of money for his family if he took part in a deception orchestrated by L to test how Kira kills. The broadcast was being shown live in different areas at different times, and the time that Kira killed Lind L. Tailor revealed that he was in the Kanto region of Japan. L declares Kira nothing more than a murderer and challenges Kira to kill him for real, but of course, without a name or a face. Light can’t. We now know two things about L: he’s a detective who has quite a lot of cachet with Interpol and the Japanese police, and he’s brilliant.

Following this, Light goes on a date to an art museum with Shiori, then Light goes into the Japanese police database to find information on L. There isn’t any, but he does find the Kira Task Force’s latest findings—that they believe Kira to be a college student. He responds by scheduling deaths so that there’s one every hour, 24 a day, which leads L to realize that Kira has access to the police database and must be connected to a police officer. He has FBI agents assigned to investigate suspicious parties, with Raye Iwamatsu being assigned to Light.

Light discovers that he’s being followed when Ryuk suddenly avoids eating apples in public, having noticed Raye but not bothered to inform Light. He then offers Light the power of the Shinigami Eyes—a power that allows a Notebook user to see other people’s true names and how long they have to live. However, this power comes at the price of half of the Notebook user’s remaining lifespan. Light refuses to sacrifice any of his own life and comes up with his own plan to discover his tail’s name.

First, Light corners Raye by taking Shiori on a date that requires that they travel by bus so that he can confront Raye once the bus is in motion. Raye gives up nothing, but then the bus is hijacked by an escaped bank robber. Light writes a note telling Shiori that he’s going to try to jump the hijacker, holding it up so that Raye can see it too. The FBI agent immediately jumps in to stop a civilian from getting hurt, holding up his ID to get Light to trust him, thus showing Light his name. Light then drops the note, which the hijacker picks up. Before he can turn his gun on Light, he notices Ryuk; Light wrote the plan on a piece of paper from the Notebook and, as Ryuk previously explained, only people who have touched the Notebook can see him. The hijacker shoots Ryuk repeatedly in a panic—which does nothing—then flees the bus and is hit by a car and dies.

His death reveals that the whole thing was set in motion by Light to get Raye Iwamatsu’s name. The only difference between this and Death Note is Light being on the bus with his steady girlfriend Shiori rather than a girl from his class he picked more or less at random.

Light then uses Raye’s name to orchestrate the deaths of all the FBI agents working in Japan. Once Light’s purpose for him is fulfilled, Raye steps off of the train and dies. With the exception of Naomi Misora being added to the scene, the entire train sequence is almost word-perfect faithful to the manga, right down to Light lowering his hood and grinning wickedly for Raye to see as he dies.

There’s also a brief scene with Misa Amane in the second act, where she hosts a cooking show and then, in an interview, expresses her admiration for Kira before being cut off by her manager. She blows her nose before leaving and the tissue is stolen by a stage manager. This scene is original to the movie, as Misa did not appear in Death Note before she had a Notebook.

The deaths of the FBI agents reveals that Kira is willing to kill officers of the law who pursue him as well as criminals, so Soichiro Yagami informs his staff that if they are afraid for their lives, they are free to leave the Task Force with no consequences to their jobs. He starts the third act with only six officers, as was true in the manga. L is so impressed with their conviction that he offers to meet them face-to-face, to extend to them the same trust he needs from them. They meet up at L’s hotel room, where we finally see the enigmatic detective: a slovenly young man who behaves oddly but displays great brilliance as a detective and asks them to call him by the pseudonym Ryuzaki. L watches multiple security camera videos at once to find Raye Iwamatsu’s death and notices that he was looking at somebody on the train as he died, somebody that he recognized. His suspicions return to Light Yagami, who Raye was tailing.

Meanwhile, Naomi begins her own investigation, tracking the people who Raye was assigned to follow, including Light. When she investigates the busjacking and hears about the busjacker’s odd behaviour, she is the first person to theorize that Kira can kill people using methods other than heart attacks. She also realizes that Kira can control the actions of his victims before their deaths, and figures all of this out without having access to the Task Force’s informationt.

Light sees that somebody has been in his room while he was out and discovers his house is bugged with video cameras. When he asks Ryuk to find the cameras, Ryuk initially refuses, until Light explains that, as long as the cameras are in the room, he can’t feed Ryuk any apples, which immediately gets Ryuk’s assistance.

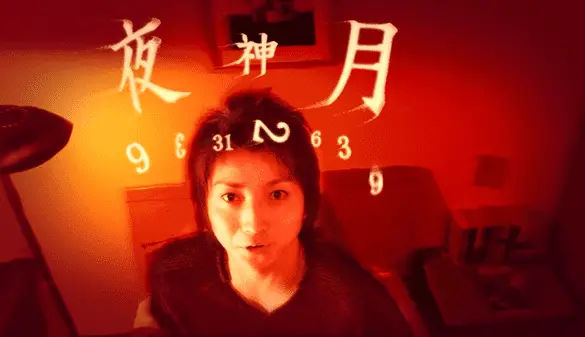

While the cameras are in his room, Light concocts a plan to make it look like Kira is killing at a time that’s impossible for him and, bless Nippon TV, they showed Light’s most infamously weird plan. Light buys a tiny portable TV and hides it in a bag of chips that only he likes the flavor of, locking himself in his room to do his homework, eat chips, and apparently not be near a TV at all while the news is reporting on Kira’s crimes.

After all of this, L has to agree to Soichiro’s demand that the cameras be removed from his family’s house. While they’re doing this, though, Naomi confronts Light in front of Shiori, declaring that she knows he’s Kira and will prove it. This marks the finale’s sudden departure from the manga’s sequence of events, as Naomi originally had no clue that Light was Kira. She ran into him by mistake and did not survive the meeting due to being tricked into revealing her name. Here, however, she keeps her name a secret and embarks on her own plan to bring Light down.

A couple of days later, she kidnaps Shiori and promises L that she’ll soon give him the proof he needs. When Light meets up with Naomi and Shiori at a museum—the one that he and Shiori had visited in the first act—he protests his innocence despite Naomi threatening to shoot Shiori if he doesn’t confess. They are all briefly distracted by the sound of sirens outside, and Shiori takes the opportunity to try to flee, but Naomi shoots her. Shiori dies in Light’s arms after kissing him one last time. As Light sobs over Shori’s body, the police storm the museum and Naomi, horrified by what she’s done, shoots herself.

Soichiro tries to comfort Light as Shiori’s body is taken away, but eventually goes to talk to L. After Soichiro leaves, Ryuk tries to get a dig in at Light for not always being in control, only for Light to look up, and with a chilling expression, explain that he controlled the entire situation, writing out the whole sequence of events, just as he did the busjacking. Due to the scarcity of guns in Japan, he knew only Naomi would have a gun in the museum, and the two deaths would interweave just as he planned. Ryuk is as impressed as he is shocked at Light’s callousness in cutting out the best part of himself, his relationship with Shiori, in favor of being Kira. All of this was possible because of Death Nippon adding Naomi to Raye’s death scene. This minor alteration to an otherwise faithful scene adaptation had enormous significance to the way the plot spins off in its own direction.

We cut to one last scene with Misa. A stalker is cornering her on a dark street at night, telling her with an eerie cheerfulness that he’s going to kill her and then himself, sending them both to heaven with her parents. When Misa screams and begs for help, the stalker drops dead of a heart attack and a Notebook drops to the ground at her feet, one with a different cover from Light’s.

Finally, we return to Light who is playing up his grief and begging his father to let him join the Task Force. L walks in, cheerfully welcoming Light to the team. He then pulls him out and eats a bag of potato chips, the exact same brand and flavor as Light used for his Potato Chip Gambit, all without breaking eye contact with Light. The two rivals stare each other down without a word, a powerful image to end the movie on.

Everything in the third act from Naomi’s confrontation of Light onwards is Death Nippon original. This seems like a significant departure from the second act’s strict fidelity to the source material, except it’s narratively entirely consistent with the work done in the first act to make Light start out as a gentler and more loving person than he was in the manga, all to make his betrayal of Shiori utterly fucking savage.

Other aspects were geared towards giving Naomi more screentime and a more active role. This not only plays on how popular of a character she is despite her short time in the manga, it also makes Light fall much further, much faster than he ever did in the source material. The movie faithfully adapted Light’s most iconic early plans—the busjacking, the murder of the FBI agents, and of course, the potato chip plan—while expanding on a fan favorite, making the movie extremely popular with fans of the series. Rather than just hopping from iconic moment to iconic moment, however, it put the work in to make the movie narratively coherent a s a whole. This made it popular with those who were less familiar with the manga, but who enjoyed a strong, complex supernatural crime drama.

How do they compare?

I find it very interesting that both adaptations focus their third acts around Light constructing a plan to protect his own innocence that involves him betraying and murdering his girlfriend, both functionally original characters. As noted in part one, Mia and Shiori are almost completely opposite characters, which changes how Light’s plans play out on screen. Shiori’s death is far more tragic because of her innocence and how her genuine feelings were used and betrayed. Mia and Light betraying each other doesn’t hit as hard because there’s nothing between them but the Notebook. Mia’s death also isn’t really a marker of Light crossing a line into true evil because she threatened him; his behavior is therefore borne out of desperation and fear. In Death Nippon, however, Shiori’s survival isn’t a threat to Light’s life or freedom, so him choosing to sacrifice her in order to shore up his own innocence, garner sympathy, and get rid of Naomi is truly evil, enough to unnerve even Ryuk.

The plot of Death Nippon is also predicated upon Light, now a law student specifically, becoming disaffected with Japan’s corrupted legal system, which leaves him open to using the Notebook’s power. Death Netflix does make a nod towards Light having issues with systemic corruption and indifference, but Death Netflix isn’t interested in exploring the problems with the American judicial system or how they influence a kid who has the power to bypass all of that to mete out justice (an exploration that probably would have only been, at best, ineffective with a white son-of-a-cop protagonist anyway).

Light briefly argues against taking suggestions from the internet on who to kill because there’s no real way to know if they’re guilty or not. But, he later use the same website to select the two criminals that he uses as part of his plan to kill Mia with no time to research them. The narrative glosses over this part of his plan, though, meaning there’s no sign of moral decay demonstrated by his being willing kill people accused of crimes without evidence.

Ultimately, Death Nippon stayed faithful to the source material, with alterations designed to plot a steeper fall from grace for Light over the course of the film. Death Netflix aimed to make its own original story, but it based that story around action and gory death scenes, leading to the characters falling apart as they were dragged from action to action without any internal consistency. The result is that the story simply doesn’t work, and wasn’t worth replacing what made Death Note so famous in the first place.

Themes

One of the things that made the original Death Note so powerful was its complex themes that still provoke questions to this day. Did the Notebook corrupt Light because power is corrupting, or because specifically the power to cause death is evil? Was Light never good at all but because his society so highly valued the importance of appearances, his intelligence and ability to play the part expected of him meant his wickedness would never have been apparent had he not received the power of the Notebook? What do societal standards have to do with morality? Is capital punishment ever justified? How important is due process, and how strong are the judicial systems that we use? What lines are acceptable to cross in the name of justice?

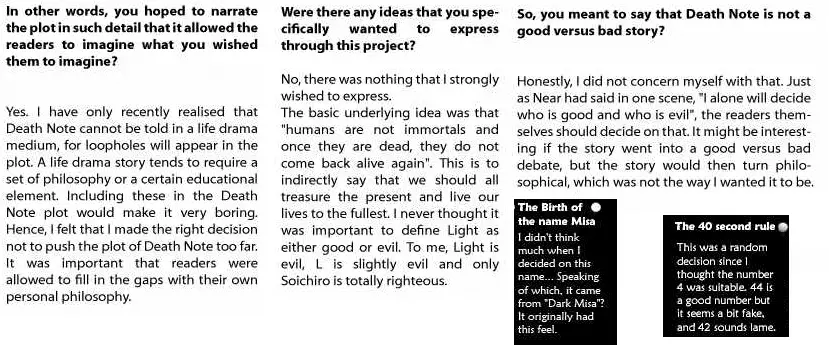

Power and justice were both keystones to the entire run of Death Note, as well as love and trust. Ultimately, the way Light isolates himself and uses others fails because of the teamwork of the Kira Task Force. The manga can be read as a criticism of the Japanese justice system or of strict societal and moral standards. It’s worth pointing out, though, that writer Tsugumi Ohba has said that he planned no particular themes for Death Note, stating in the supplementary How To Read book that “no human has the right to pass judgment on another’s actions. No one should play God.”

Death Nippon turns Light into a law student at university in order to specifically highlight the troubles in the Japanese justice system as a major part of why Light becomes Kira and also why Kira enjoys such wide public support. Japan is an extremely image-based society, one where many people put up public fronts that are wildly different from what they actually think and feel in the name of acceptability.

Light plays this perfectly, portraying the ideal college student while secretly being a mass murderer. Light throws away his law book and takes up the Notebook, starting a moral decline that leads him from killing criminals to killing FBI agents and then the entirely innocent Shiori. L is his exact opposite; he defies strict social conventions by greeting and talking to people impolitely, eating and behaving in bizarre ways, and dressing inappropriately. But at his core, he is a deeply moral person who truly believes in justice and that killing is wrong.

Death Nippon may, simply through greater intention, have a stronger thematic base than Death Note does. Due to the way that the scene where Light first hacks into the police database–something he does before he has the Notebook–is handled, with a heavy focus on the huge number of criminals who went free on technicalities, the movie definitely has a very deliberate condemnation of the Japanese justice system built into it. However, the acceleration of Light’s moral decline into murdering Shiori prevents this from in any way making Light circumventing that system more sympathetic.

Death Netflix’s themes, on the other hand, are… ummm… killing is wrong? I think? The lack of any discernible moral decline for Light or Mia makes it hard to argue for a “power is corrupting” theme. Light doesn’t change in his position of “kill bad guys but don’t kill innocents or law officials” from beginning to end, and nor does Mia change on her “kill whoever the fuck you want” stance. The attempts to sell Light and Mia as in love with each other fall so flat that it can’t really be said that their love was tragically corrupted and destroyed by the Notebook, though the soundtrack certainly seems to be trying to make that a thing.

As mentioned above, there’s no examination of the very real problems with the American justice system, just a couple of token complaints from Light that don’t become anything more. The way L’s position as main antagonist is given to Mia and how his own morals are entirely disregarded in favor of having him chase Light with a gun means that there’s no really effective “extrajudicial killing is always wrong, even when they’re criminals” balance for Light. There’s no particular conflict between societal expectations/appearances and Light and Mia’s behavior (just the opposite in face, if you read part one).

Between the high-budget, lovingly constructed death sequences and the way that even L is ultimately tempted by the power of the Notebook, the theme of the story might be that “killing is cool”, which is probably not the most socially conscious message for a movie aimed at teenagers and young adults in the only first-world country where domestic mass shootings happen on a weekly basis.

In Conclusion

Both movies end with Ryuk quoting himself from the manga in response to Light’s behaviour. At the end of Death Nippon, Ryuk, in response to the sheer evil of Light murdering Shiori, solemnly tells him, “you know what, Light? You’re worse than any shinigami.” By contrast, the Ryuk of Death Netflix, after listening to Light Turner describe how he murdered his girlfriend, cackles out his much more famous catchphrase, “humans are so… interesting!” Light Turner murdering his girlfriend is cool and interesting; Light Yagami murdering his girlfriend is evil enough to horrify a god of death.

Both plots are entirely original to the movies, and the endings oddly similar for how ultimately opposite they turned out to be. The end result is that, wile Death Nippon was clearly timed to capitalize on the massive success of Death Note, director Shuusuke Kaneko at least understood and cared about the story and themes of Death Note enough to utilize and expand on them, while Adam Wingard somehow managed to actually care less about the meaning of Death Note than its own creators.

On that note, Ohba and Obata were in fact full of praise for Death Netflix, particularly its aesthetic. With neither the characters nor the story having much to do with the original work, at least Wingard adapted enough of the iconic imagery and script to make a work that’s recognizably Death Note, right?