Introduction:

This Queer History Month, I want to discuss how bisexual art intersected with the Disney Renaissance. The character Hercules would be an easy mark, since the animated musical straighwashes the mythic hero’s unabashed bisexuality. But I want to focus on real bisexual people whose work helped form the foundation of The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast (BatB). I’m specifically focusing on Hans Christian Andersen and Jean Cocteau, two bisexual men whose dual desires brought them alienation, angst, and artistry.

Unsurprisingly, some of our beloved childhood classics are pretty gay bi.

Before diving into bi culture, I need to lay out the inherent queerness of the two films themselves. Howard Ashman, an out gay man, worked as the lyricist for both films. But Ashman couldn’t be contained to lyrics. He worked as a producer for The Little Mermaid, writing some additional dialogue. He was also an executive producer for BatB, and he helped redevelop the script, being the one to suggest the movie be a musical and to make the Beast the second protagonist. Vanity Fair described Ashman as a “shadow director on the Disney projects he undertook,” so it would be an understatement to say that Ashman was involved.

He poured his experiences as a gay man into these works. The Little Mermaid addresses a forbidden love and a silenced identity, parental rage and misunderstanding. Animators also used Divine, a drag queen, as a model for Ursula. (Divine was the stage name of Glenn Milstead, a gay Baltimorean like Ashman himself.) BatB, on the other hand, addressed societal outcasts, the raging mob of ‘concerned citizens’, and illness. The Beast’s curse, further personified by the fragile enchanted rose, served as a clear AIDS metaphor. (Ashman died from the disease while the film was still in production.)

The Disney variants as we know them have encoded queerness. But they were building on queer contexts — Ashman and Co. only enhanced what was already there through Andersen and Cocteau’s works.

~

Attributing modern labels to historic figures can be ~problematic~. For one thing, often these labels would have not been available in their current definitions, if they had even been invented yet. Our Western, anglicized concept of sexuality does not apply across the board. But gay and straight people attribute their modern labels to historic figures all the time, so as an improper bisexual I will do what I want. Bisexual people have been erased from history too often, especially bisexual men due to toxic masculinity and homophobia. Male bisexual activists have even compared this to the “one-drop rule” that racists used during the Jim-Crow era. In terms of male sexuality, it’s the one-drop of gayness to divide straight men from anything associated with femininity.

With all of that in mind, the queer and bisexual elements of their works are not exactly the same. Andersen created his story wholesale, while Cocteau adapted a fairy tale traditionally by and for women, inserting commentary on masculinity.

Andersen & Gay Angst:

The Disney Renaissance began in late 1989 with the release of The Little Mermaid. As we all know, it smashed the box office, soaked in critical and commercial acclaim, and won two Oscars. And Ashman’s Broadway background shaped the film and laid the groundwork for the musical theatre style that became the now-satirized Disney formula. As with most Disney properties, The Little Mermaid was an adaptation of literature already in the public domain. One sad boi poured his heart out and gave us a lovestruck mermaid since he couldn’t kiss the boy.

Born in Denmark in 1805, Hans Christian Andersen authored several classic fairy tales throughout his life. His publications include ‘The Ugly Duckling’, ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’, ‘The Snow Queen’, and of course ‘The Little Mermaid’. Andersen was a spiritual man and swore off relationships, romantic and physical, but those private vows could not stop him from catching feelings. His attraction to men and women is well-documented, including his proposal-by-letter to Jenny Lind, a famous Swedish singer, and his gushing correspondence with Edvard Collin.

Andersen wrote ‘The Little Mermaid’ in 1836, and the story was first published as a part of a collection of children’s stories the following year. It detailed a young mermaid’s interest in the human world, nurtured by her grandmother and older sisters’ stories of the surface. Much like in the movie, she rescues a human prince from a sinking ship, but in the original version, a human girl finds him on the beach when he regains consciousness. (She would be reimagined as Ursula’s human disguise for the film.) The mermaid then does seek out a sea witch and succeeds in transforming into a human on a deadline. This sea witch is a neutral character at worst. Her deal comes at the cost of the mermaid’s voice, but being a fairy tale, the price also includes constant physical agony and the risk of death.

In Andersen’s imagination, the merfolk lack eternal souls, condemned to nothingness after dissolving into seafoam when they die. The story ends semi-tragically as the prince ends up in an arranged wedding with the human girl from earlier, a princess herself. The sea witch offers the mermaid an out and a return to her old life by killing the prince with an enchanted dagger, using his blood as an antidote to give her back her fins. The mermaid instead chooses to dissolve into seafoam as she cannot kill her love.

But Andersen does not completely destroy his heroine. The story concludes with the mermaid now a ‘Daughter of the Air’ and able to earn an eternal, Heaven-bound soul if she performs good deeds for three hundred years. It’s an ending, to say the least.

Gay historian Rictor Norton theorizes that Edvard Collin’s marriage to a woman and Andersen’s subsequent heartbreak inspired the story. Norton points out that Andersen wrote the fairy tale around the time that Collin decided to get married, explaining, “Andersen displays himself as the sexual outsider who lost his prince to another,” (p. 129). Of course the Internet loves this theory, and a viral ‘factoid’ claims that Andersen even sent the story to Collins. But from what I’ve found, that’s more Internet fanfiction than anything else.

The story’s queerness, though, is not in dispute. Andersen experienced attraction to more than one gender and that would have colored his writing, his experience of the world, and ultimately his choice of character in the Little Mermaid. Liminal, fantastical creatures and symbols have long been associated with the queer community. Sacha Coward has researched mermaid imagery in numerous museums and notes that,

“Unicorns, mermaids, fairies and other beings that mix and combine features have long become popular with queer people[.] […] One reason may be that LGBTQ+ people feel like they only half belong, that they are not quite of this world and their existence seems to blur the lines between societal norms of masculinity and femininity.”

For the bisexual community, these kinds of symbols bear even more meaning, as the bisexual experience encompasses a kind of uncertainty — rooted in fluidity, invisibility, and an in-betweenness. How society views us as half straight and half gay. Mermaids, unicorns, crescent moons; these symbols all have connections to bisexual culture, partially for those reasons, the latter two with direct cultural relevance in the bisexual community. This invisibility, and subsequent erasure, forms such a core part of the bisexual experience that it was incorporated into our flag through symbolic gesture.

Mermaids with their liminal bodies, both human and animal, fall into this broad category. The mermaid has her own resonance for a silenced individual who struggles to feel belonging in a binary world. In a 1974 essay, Louise Knox lamented, “A lesbian at a feminist meeting tells me I’ve got “the new disease.” I’ve just told her I’m bisexual. […] For all the credibility I get, I might as well be calling myself a centaur or a mermaid.” Andersen may have been the first known bisexual to use the mermaid, but he was not and will not certainly be the last.

Cocteau Considers Masculinity:

Unlike ‘The Little Mermaid’, BatB has a long, complex history in Western literature, as does many a fairy tale. Disney’s adaptation is no exception.

Disney released Beauty and the Beast in 1991 and dedicated it to Howard Ashman. As we all know, this animated musical smashed at the box office and won two Oscars, like its predecessor. What’s not as well known is that Disney took some of its narrative and aesthetic cues from Jean Cocteau’s 1946 film, La Belle et la Bête. The former film struggled to get off the ground in the late 80s but within those developmental issues some of its bones started to form. Screenwriter Jim Cox wrote two treatments and even a finished screenplay for the Mouse, pulling inspiration from Cocteau.

While Disney ultimately rejected Cox’s screenplay, he retained film credit for ‘pre-production script development’ and Cox’s artistic decisions can be still felt in the final example. For example, it’s generally agreed upon that Cocteau’s character Avenant inspired the character of Gaston. Before La Belle et la Bête, there was no chauvinistic suitor to contrast against the Beast’s dichotomous, empathetic nature (Cummins p. 27). Some contemporary critics even noted Cocteau’s influence on the Disney version.

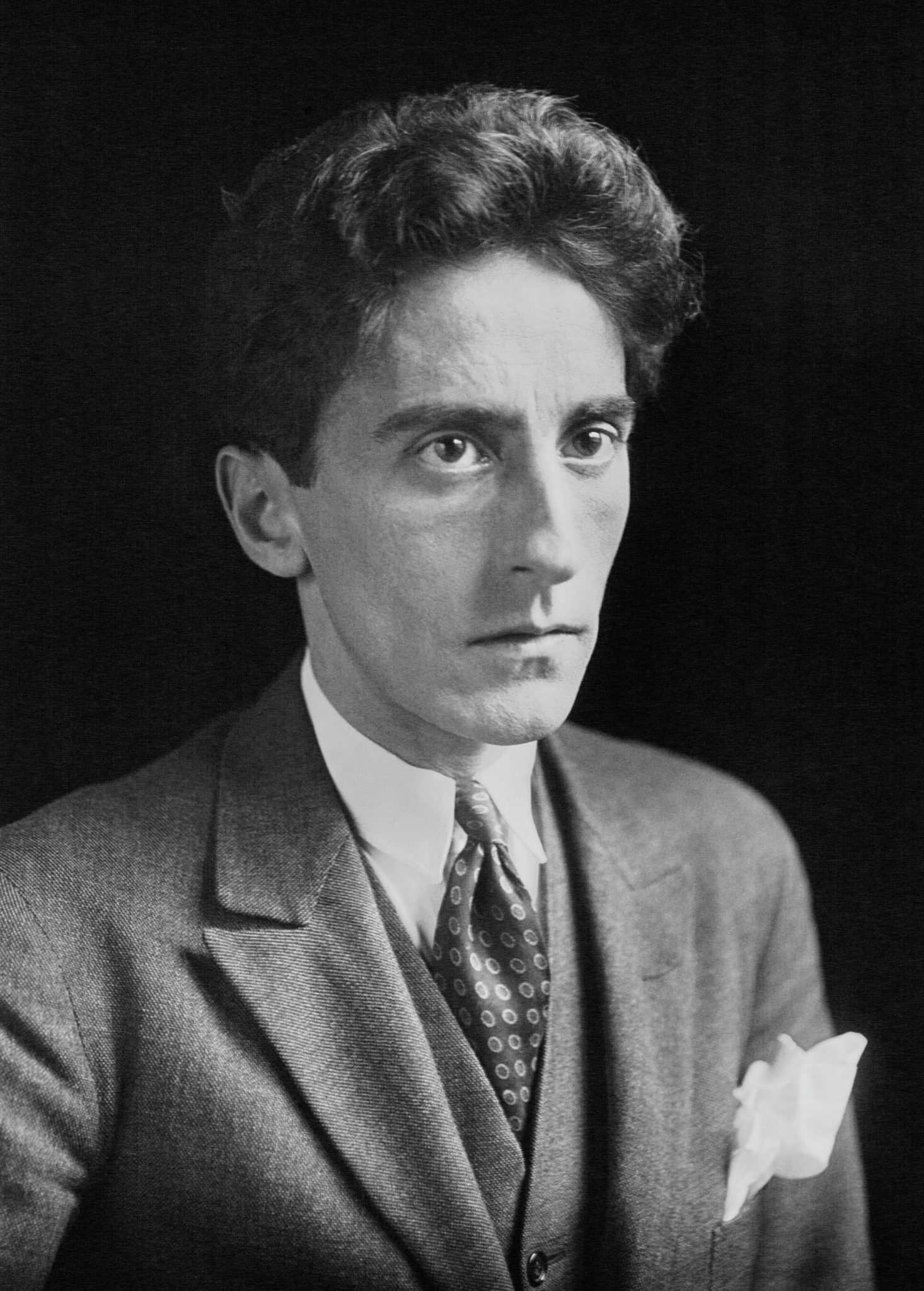

Jean Cocteau was born in France in 1889. The French creator worked in various mediums, though today he is best remembered for his films, several of which are now considered classic cinema. He was relatively openly about his relationships with men, when considering the time; so much so that gay readings of his work aren’t controversial. Many people consider him homosexual, and so did I for a long time. I first learned about Cocteau when researching BatB for a school project four years ago, and all my scholarly sources asserted that Cocteau was ‘gay’ in the exclusive way we think of it today. Recently though, I learned that Cocteau had relationships with women throughout his life as well, which biographers acknowledged were passionate and romantic. Cocteau happened to have a preference for men, it seems, and his most prominent relationships were with men. But to biographers, that meant Cocteau was gay, with one biographer even asserting this while writing about Cocteau’s “later protestations of bisexuality” (Arnaud p. 50).

I didn’t even know about Cocteau’s possible bisexuality until I happened to see his name on a list of ‘Famous Bisexuals in History’ this summer. But when I saw his name and considered a bisexual person making La Belle et la Bête, that made sense to me intuitively because of the film’s themes and aesthetics, its play with duality. In a recent rewatch, I considered how the film arguably has a bisexual gaze, equally valorizing a feminine aesthetic in Belle and a masculine aesthetic in the Beast. Bisexual culture also has its own relationship to gender fluidity and contemplation, so it’s no surprise that Cocteau’s film addressed toxic masculinity.

As I discussed last year, Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont wrote the most influential version of Beauty and the Beast, which itself was an abridged adaptation of a longer, more complex novel. She released her children’s story in 1756. Almost two hundred years later, Cocteau adapted Leprince de Beaumont’s children’s story into a screenplay. He subsequently directed the 1946 fantasy romance and captivated moviegoers, the war-weary French psyche affected by its sincerity, escapism, and theme of redemption. The Arts Shelf described La Belle et la Bête as “Cocteau’s spellbinding, sensuous masterpiece.”

The film generally follows Leprince de Beaumont’s story, with embellished plot and visual elements. A wealthy merchant loses his ships in a storm and, having fallen into poverty, he is forced to move his family into their country home. The self-sacrificing, humble Belle contrasts against her vain, envious sisters. While they ask their father for gifts of luxury, Belle requests only a rose. As the story goes, the merchant gets lost on his way home and takes shelter in a shadowy, enchanted castle. He takes a rose from the garden and incurs the Beast’s wrath, who demands the father’s life or that of his daughter’s as retribution. Belle goes in her father’s stead. Much like the fairy tale and the Disney version, La Belle et la Bête then builds a romance around sharing meals, spending time together outside, and the Beast letting Belle go see her family.

The story’s climax comes with Belle returning to the castle in a panic to find the Beast, who she discovers while he is dying from heartbreak. And as we all know, her love revives him and breaks the curse. Cocteau adds an element of complexity to her reaction to the Beast’s transformation but it just makes the film that more relatable. Cue the ‘happily ever after’ moment and the tissues.

That being said, Cocteau distinguishes his retelling by using the second half of the movie to explore the Beast’s inner conflict. Cocteau’s adaptation sets off the shift in BatB stories where the Beast’s character development is central, rather than the Beauty’s, which resonates in storytelling today. The character struggles with his animal instincts, and Belle’s physical vulnerability, coupled with the Beast’s nocturnal visits at her bedroom door while in a frenzied state, give those animal urges a sexual element. Cocteau is making a statement on how empathy affects masculinity and aggression. He stresses this by including a counterpart to the Beast.

As I mentioned earlier, the character of Avenant addresses male aggression and laid the groundwork for Gaston. Belle has an irresponsible brother, Ludocvic, who further pushes the family into debt. In Leprince de Beaumont’s story, Belle did have a brother. Cocteau added a friend of the brother, Avenant, who is occasionally like a Devil on Ludovic’s shoulder.

Avenant, a self-avowed ‘scoundrel’, proposes to Belle early in the film, and after she refuses, he attempts to force a kiss on her. When she returns from the Beast’s castle, he refuses to listen to her defense of the Beast’s character, insisting that she must be under a spell. At the end of the film, Avenant and Ludovic then attempt to break into the Beast’s pavilion of riches, and while Ludovic hesitates, Avenant breaks the glass ceiling. As he attempts to climb down, a statue of Diana comes to life and shoots him with her arrow, killing him. Avenant’s body transforms into the Beast, while the Beast transforms into the Prince, now an Avenant with short hair. The Prince declares, “Love can make a Beast of a man. It can also make an ugly man handsome,” and drives home Cocteau’s point on empathy, an ingredient in love. Many scholars even interpret Avenant’s trespass as a symbolic attempted rape, bolstered by his previous mistreatment of Belle and by the fact that Diana is the goddess of chastity.

Disney simply took Cocteau’s addition of a human suitor and exaggerated his toxic masculinity, making the implicit explicit.

Regardless of what Cocteau’s sexuality would be considered today, bisexuality factors in the creation of La Belle et la Bête. He had his lover of many years, Jean Marais, as the male lead. Marais starred in a triptych role; playing as the Beast, Avenant, and finally as the Prince. Marais was an openly bisexual men and is remembered that way. (Two bisexual people of the same gender in a relationship, shocking, I know.) Marais was the one who suggested to Cocteau that he should adapt Madame Le prince de Beaumont’s fairy tale into a film. While it’s impossible to know if Marais chose BatB specifically because it spoke to his bisexuality, that aspect of his personhood cannot be discounted.

Two bisexual men helped to create a cinematic classic and helped to lay the foundation for another masterpiece. And the film remains influential today. It influenced Ron Koslow’s 1987 Beauty and the Beast TV show, and George R. R. Martin listed La Belle et la Bête in his top ten favorite films. You can see Cocteau’s commentary on masculinity in Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire book series. Martin subverts the BatB trope in different ways through two relationships: Sandor Clegane and Sansa Stark, and Jaime Lannister and Brienne of Tarth. The two pairings both have themes related to the rigidity of gender roles and the corrosive effects of toxic masculinity and benevolent sexism.

The British Film Institute also released a restored print to cinemas in 2014 and brought it to a new generation. Though Disney has the wider reach on culture between its BatB and Cocteau’s, there is something comforting about the fact that one movie can still reverberate decades later. That the bisexual experience can manifest in art without relying on an explicitly queer romance.

Conclusion:

All of that in mind, the Mouse’s bisexual representation remains scarce, with the bulk of it concentrated the Disney Channel. And the company has always had a ~complicated~ relationship to its stories’ queer themes and to its supporters from the queer community. There is a difficult history of villainous queer coding, queerbaiting, and erasure.

But things are getting better — not as fast as we would like them to — but steps forward are being taken. For example, late this summer The Owl House released its prom episode on the Disney Channel, and the show’s openly bi creator confirmed that her main character is bisexual. (I’ve spent this past month gushing about The Owl House to anyone who will listen.)

I think one way Disney can improve on its representation and its relationship to the queer community is by acknowledging the queer history that shades the company in bright colors. That history would include honoring the creators within those colors.

And to our Disney-loving readers, happy Queer History Month!

Images courtesy of Disney, Wikimedia Commons, and Pixy

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!