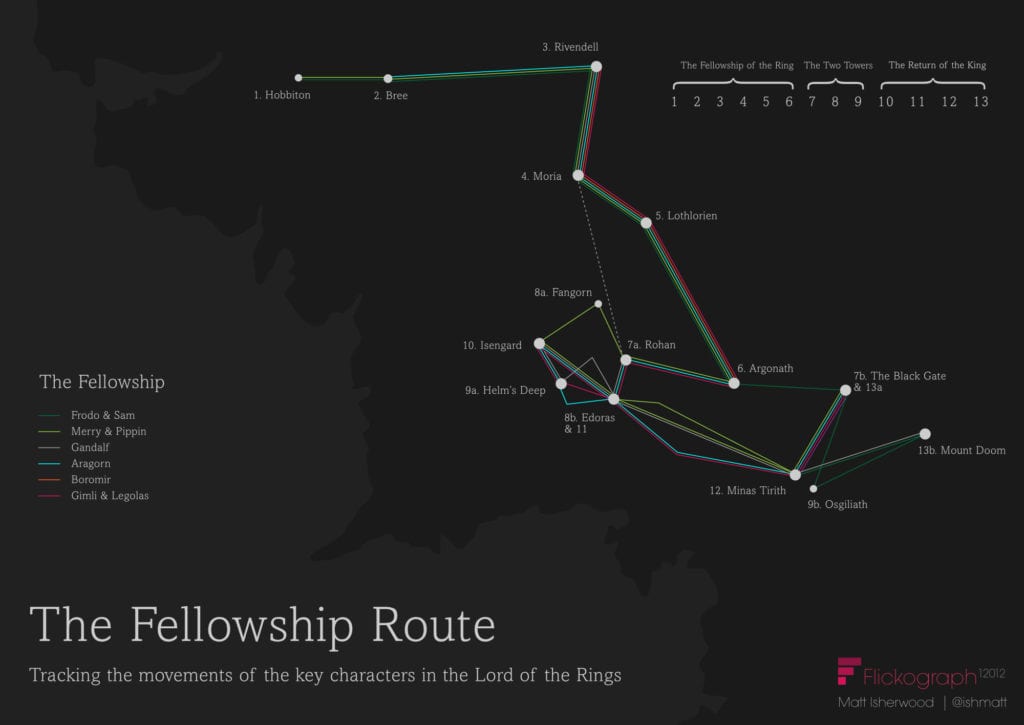

The Fellowship of the Ring is a very goal-oriented story. It’s a classic mission structure (and in many ways, strongly parallels The Hobbit). Once we get our info dump in “The Shadow of the Past” the narrative has a strong, linear focus: get the Ring to Rivendell, form the Fellowship, get the Ring to Mordor. It’s a simple story—despite the mountains and ages of history that lie behind it—and a lot of the reader’s enjoyment comes from following a unified group jump from set piece to set piece. Rivendell, Caradhras, Moria, Lórien. It’s easy to guess a bare-bones outline of what’s coming next by looking at a map.

The Two Towers upends this formula. It does it geographically. Rather than moving towards a specific place, Aragorn and Company have spent the last seven chapters zig-zagging around Rohan. It does it structurally. Frodo and Sam have been out of the equation for 175 pages, with no one knowing what happened to them. And it even does it on the level of character and plot. The characters themselves don’t know what they’re doing, and react to things in the moment as best they can. It’d be hard to guess, as Aragorn, Gimli, Legolas, and Gandalf sat and chatted in Fangorn Forest, that an all-out battle would happen thirty pages later.

This could have been to The Two Towers’s detriment. A lot of middle chapters in trilogies run into similar issues: too much bloat, not enough focus, setting up pieces for the end rather than telling a cohesive story. Back to a map perspective, rather than feeling like things are moving forward, there’s a sense of running in circles.

But I think it works. From the start, The Two Towers has been about quick, necessary choices, and the burdens of unlimited possibilities. Aragorn’s character arc has been about coming to terms with them; Gandalf highlighted Sauron’s and Saruman’s greatest weaknesses as their decision to ignore them. It makes this installment feel more frantic, fraying, as if the whole endeavor could quickly fall apart at the seams. Even before the battle begins, our heroes seem one step behind everything that is happening, scrambling to catch up. “Helm’s Deep” is the clearest example of this so far. And it is a good example of how The Two Towers is a more anxious, restless, and spontaneous book than its predecessor.

Retreat to Helm’s Deep

The beginning of “Helm’s Deep” verges on tonal whiplash. Whereas the end of “The King of the Golden Hall” was triumphant, its successor quickly calls that optimism into question. As the Rohirrim make a dash towards the Fords of Isen, where other Riders are holding the line against Isengard, things begin to look more and more ominous. A “growing darkness, as of a great storm moving out of the East” rises with the sun, and afternoon clouds, “a somber canopy with great billowing edges flecked with a dazzling light”, slowly shift over them. Gandalf sees a darkness in the distance and leaves abruptly; news arrives that the Rohirrim have been routed at the Fords and are making a chaotic retreat to Helm’s Deep.

It’s a sharp downhill plunge, and things only get worse. As the Riders make their way towards the mountains to reinforce the Keep, they find themselves essentially in the middle of the retreat. Dead kinsmen are strewn on the ground around them, companies are scattering in chaos, and some wolf-riders and orcs are already present. I’d forgotten how bad this looks for everyone. Helm’s Deep isn’t a calculated stand at an impenetrable fortress. It’s more like a desperate fleeing to the mountains after things have already gone very, very wrong.

Scattered Like Red Flowers

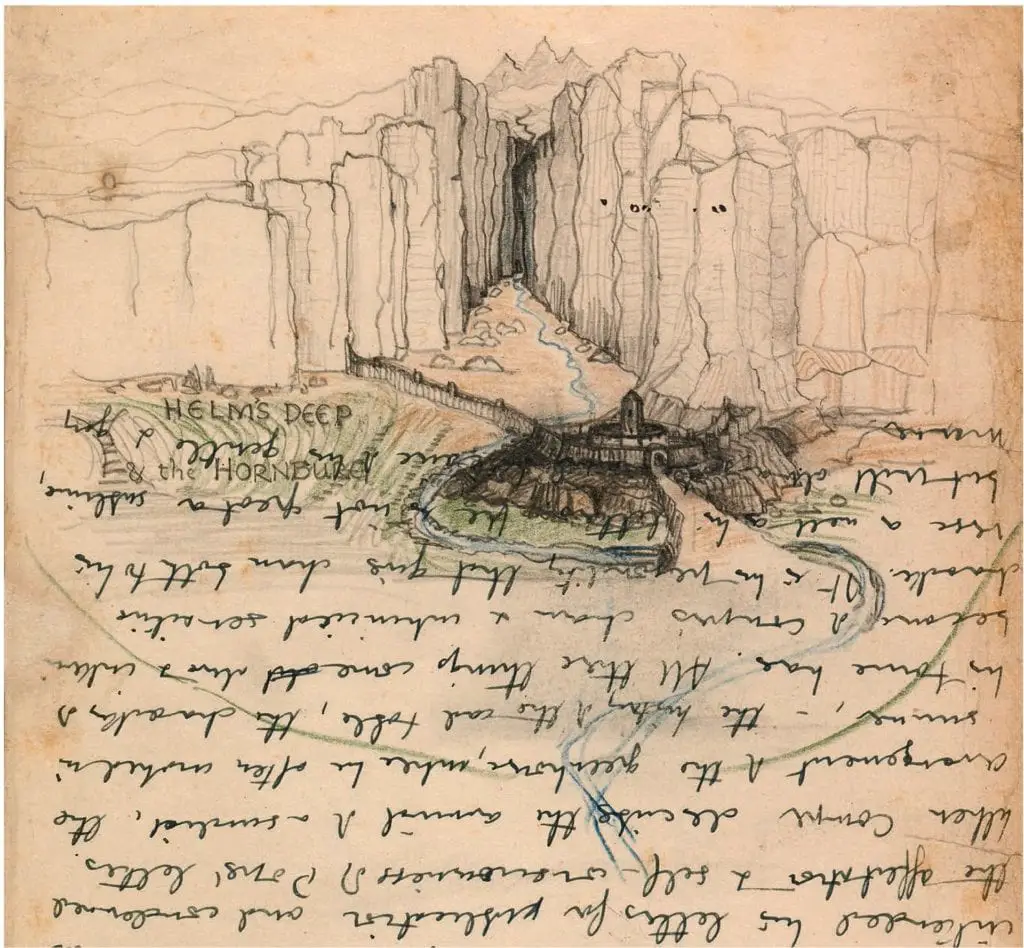

Because of this, Helm’s Deep doesn’t feel all that comforting. It should—the place is tough enough to have inspired speculation that it was built by the hands of giants, and its horn echoes in the surrounding mountains so loudly that it sounds like armies spilling out from the hills. The Deeping Wall is twenty feet high and so thick that four men could walk abreast across the top. It’s not the Theodosian Walls, but it’s still impressive. Rumors claim that it could never fall to assault but people said that about Constantinople too.

So even when the Rohirrim have reached Helm’s Deep, things still feel dire as a massive army encroaches close behind:

“Now they could hear, bourne over the dark, the sound of harsh singing. They had climbed far up into the Deeping Coomb when they looked back. Then they saw torches, countless points of fiery light upon the black fields behind, scattered like red flowers.”

And later:

“Then the Orcs screamed, waving spear and sword, and shooting a cloud of arrows at any that stood revealed upon the battlements; and the men of the Mark amazed looked out as it seemed to them, upon a great field of dark corn, tossed by a tempest of war, and every ear glinted with barbed light.”

I love these analogies so much. They work on a purely literary level, drawing a tie between the discordant ideas. They are very pretty and delicate images when so much of the surrounding reality is cold rain and dark stone. But they also take on such a playful meaning in the context of the chapter’s ending, when the orc army is literally destroyed by trees.

The orcs are compared to elements of nature on three separate occasions. Besides the two above, Legolas believes he spies them in the distance like “the twilight under endless trees.” Of course, it’s more than possible that Legolas is literally seeing the twilight under endless trees as he looks towards Isengard on this particular day. But still. It’s clever, of course, to compare the army so often to the thing that will ultimately destroy them. But it’s also very thematically fitting. Saruman’s power has always been imitative. He saw himself as creative, whether in his creation of the Uruk-Hai or in his plans to supplant Sauron. But he simply mirrored power or warped it. Because of this, it’s fitting that his army was depicted as analogies of plants before being consumed by real ones.

An Old Tree Under Winter Snow

While Tolkien is good at ramping up atmosphere and his logistics seem pretty sensible, his action sequences are not the best. Often Aragorn and Eomer just fling themselves into combat where, after some perfunctory sword-chopping, the orcs just run away. On occasion the heroes feel a little like those action figures whose arms chop up and down.

But in the end, this doesn’t matter all that much. Like so much in Tolkien, Helm’s Deep works best as an internal moral test of a character. And though he’s in the background for most of the siege, Théoden is our moral center.

He starts out the chapter on a high note. Still fresh from his victory over himself at Meduseld, Théoden is feeling confident. He takes clear joy in surprising a rider at his new healthy and vigorous state, exclaiming “You thought I remained in Meduseld bent like an old tree under winter snow. So it was when you rode to war. But a west wind has shaken the boughs.” It’s a nice image and only becomes more fun when you realize that Théoden is unknowingly likening himself to an Ent.

But as the weather turns and Gandalf abruptly disappears, Théoden begins to waver. He misses his counselors, both “the old and the new,” and seems uncomfortable being out on his own. He works as a neat echo of early-book Aragorn. And after a night of battle at Helm’s Deep, he’s even more uncertain.

“The world changes, and all that was once strong now proves unsure. How shall any tower withstand such numbers and such reckless hate? Had I known the strength of Isengard was grown so great, maybe I should not so rashly had ridden forth to meet it, for all the arts of Gandalf. His counsel seems not now so good as it did under the morning sun.”

It’s a good test of whether Théoden can hold onto his newfound hope when he has manifold reasons for doubting . And it’s another nice example of personal moral choices being the centerpiece of large-scale external outcomes. In choosing to hope—or at least not to despair—Théoden gets his reward.

And the readers are rewarded to, with a wonderful ending to the chapter.

“But even as the gate fell, and the Orcs about it yelled, preparing to charge, a murmur rose behind them, like a wind in the distance, and it grew to a clamor of many voices, crying out strange news in the dawn. The Orcs upon the Rock, hearing the rumor of dismay, wavered and looked back. And then, sudden and terrible, from the tower above, the sound of the great horn of Helm rang out.”

And after the charge:

“Great trees, bare and silent, stood, rank on rank, with tangle bough and hoard head; their twisted roots were buried in the long green grass. Darkness was under them. Between Dike and the eaves of the nameless wood only two open furlongs lay. There now cowered the proud host of Saruman, in terror of the king and in terror of the trees.”

Such an ending to a seemingly-doomed battle could feel like a deus ex machina. But in this case, there is a specific reason for everyone being there. Théoden rode against “reckless hate” when he could have stayed in the Hornburg or fled to the caves. Treebeard and the Ents could have stayed silent in Fangorn. But they didn’t. And the fact that they are rewarded for their action and persistence, regardless of the cost to themselves, is a beautiful moment, and a small glimpse of the eucatastrophes that mark The Return of the King.

Final Comments:

- Honestly, the best moment of this chapter: “I followed you to shake off sleep,” said Gimli. “But I looked on the hill men and they seemed overlarge for me, so I sat beside a stone to see your swordplay.” I truly love Gimli. What a practical battlefield ethos.

- I have generally fond feelings for PJ’s The Two Towers (though I think it’s the weakest of the trilogy). But this chapter is making me think I’ll be less kind next time I watch it. He makes a lot of weird, weird adaptational decisions.

- I do, though, find it very helpful as a visual aid. I remember as a kind having quite a bit of difficulty envisioning Helm’s Deep. I’m sure I had no earthly idea of what a “coomb” was (and had to look it up again this time—it’s a dry valley that’s easily defended). And Tolkien’s geography can be a bit disorienting. But I found it much easier going this time, with the movie as a visual starting point.

- I like that some of Théoden’s men seem wary of Gandalf, especially after his brusque disappearance. It seems fitting; for all his faults, Gríma was a man a Rohan, a known quantity, and he kept them out of war. It makes sense that some would resent an outsider like Gandalf coming in, especially when everyone finds themselves on the brink of a last-stand battle twenty-four hours later.

- Also on that note, Gandalf’s disappearance seems another nice example of him not quite being his old self. He could have averted a lot of strife and confusion if he told someone his plan before the army moved off to Helm’s Deep.

- Gimli bein’ Gimli; Legolas bein’ Legolas: Gimli talks about how much he likes rocks and how he could build an impenetrable fortress more impenetrable than the impenetrable fortress they’re already within; Legolas says that dwarves are strange, damns the Rohirrim archers with some faint, faint praise, and then says something sweet to Gimli.

- The Dunlanders at the battle are an interesting detail. Eomer is disgusted by them and views them as less than human. Háma, keeping up his greatness, backpedals from this. He suggests that they aren’t particularly bad people, just people who hold a (potentially justifiable) grudge against Rohan. It’s a nice note of moral ambiguity.

- Prose Prize: I really like the analogy of the battle to a field of dark corn tossed in the wind.

- Contemporary to this chapter: It’s a busy few days. As the Riders are leaving from Edoras on the evening of March 2nd, Erkenbrand and his forces are facing defeat at the second battle of the Fords of Isen and the Ents are beginning their march on Isengard. On March 3rd, Théoden and company reach Helm’s Deep and the battle begins, as the Ents destroy Isengard and meet Gandalf, who persuades them to help. Frodo and Sam are walking.