Introduction

Progress in media representation, while incremental, is generally linear. The Spring Slaughter of 2016 was a humongous step backwards, culling the queer women representation herd to an embarrassing fraction of what it was at the beginning of 2016. But we also have to remember that in order for that many canonically queer women to die on television, they had to be on television in the first place. The Spring Slaughter was a horrific event, and obviously I am not saying otherwise, but sometimes we have to take a step back to see how far we’ve come. I have joked before in podcasts and articles that it took the Spring Slaughter for me to look back at Glee in a favorable light, but there’s quite a bit of truth to that. At the time it was on the air, it was a show I had what could be generously described as a love/hate relationship with. But now, with 2016 in consideration, it sometimes feels like we were maybe making a problematic mountain out of a collection of problematic molehills. I mean, at least the lesbian didn’t die.

As I keep saying over and over, this is an incredibly low bar to set, but it’s one that most television shows are clearly determined to limbo right under. Because of this problem (and many, many others), it becomes difficult to recommend past content to new audiences, despite their historical importance. I have talked about before how I don’t believe that people should have to subject themselves to problematic or harmful content just for the sake of being included in the queer cultural zeitgeist. And I do believe this pretty firmly, in most cases: I cannot recommend with a straight face that anyone should watch The 100 now, especially past season two. While The L Word and Queer as Folk are hugely important historical and cultural hallmarks for the queer community, both shows have arguably done more harm than good, especially The L Word. When compared to its predecessors and contemporaries with canon queer relationships, Glee is actually quite tame in the problematic sense.

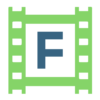

Make no mistake though, there is problematic content in Glee. Its technicolor dream coat is bursting at the seams with problems. You can see how queer culture and language shifted across its tenure, which is a nice way of saying you’re going to hear some slurs, jokes, and statements that are hurtful and upsetting, especially in its early seasons. It somehow manages to be simultaneously queer representative, queer coded, and queer baity. For every Landslide and Blackbird there is a Blurred Lines and a My Prerogative. After season three, the show is not so much a narrative as it is a collection of iTunes hits held together with gold star stickers and wishful thinking. It is one part musical theater, one part show choir, one part gay current events, and one part stereotypical teen drama. It will have you laughing your ass off, ugly sobbing, and frothing at the mouth in rage. Sometimes all in the same episode.

But despite its numerous and glaring flaws, Glee has the honor of being one of the most popular, influential, and groundbreaking television shows to ever jump into the deep end of queer representation on television. There is absolutely no denying the cultural importance of Glee for the queer community and the queer community’s public perception. It was the show that normalized queer relationships to a general viewing audience, with a family friendly rating. It is impossible to overstate how significant Glee was at the time, and how groundbreaking it still manages to be, despite its many stumbles and falls. To deny the show’s importance is to dismiss one of the key pillars that became the foundation upon which our current canon queer ships are founded. You cannot have Wayhaught and Sanvers without Brittana, just as you would have no Brittana without Tillow and so forth. If we want to see further and continue to improve queer media representation, we must do it by standing on the shoulders of giants, and one of those giants is Glee.

There are precious few people I have met on the queer spectrum who don’t have very strong opinions on Glee one way or the other. Because of this divisive nature, and because I will likely be very mean to it during the course of this article series, I want to make one thing really clear right off the bat: I actually do love Glee. I love it with all of my little gay heart, no matter how much of a mess it tends to be. I love it so much I can’t listen to “Don’t Stop Believing” without getting misty eyed. The show has so much personal significance to me as a gay woman, it can be difficult to talk about because I get choked up while attempting to articulate my thoughts. But I also believe that you can love something while being deeply and thoroughly critical of it, and Glee is definitely a show that needs to be consumed mindfully and with several grains of salt.

Now, concerning this retrospective series, a few small notes: first, I am not going to give you an episode by episode synopsis, because this show has 121 episodes clocking in at around 45 minutes each. As much as I do love writing analysis, I do have a day job and friends and a fish who needs feeding. Let me live.

Second, I am going to spend considerably less time talking about the first season than I do about the rest of the series, because my primary focus of this article series is queer representation, and season one is actually rather light on that. It is not that season one isn’t important (and I will discuss why), or that I don’t thoroughly enjoy it, but for the sake of my sanity and a reasonable word count I must keep a somewhat narrow focus. My discussion of season one is going to center a bit more about establishing tone, style, and format, rather than analysis of story content.

Third, I will talk about Faberry and its non-canon companions, but in its own article. The unprecedentedly massive fandom surrounding Glee needs, and deserves, its own separate discussion and analysis. I will get there, I promise. Just not this week.

With all of that in mind, let’s just jump right in shall we?

Season One: The Opening Medley

If you’ve never watched the pilot for Glee, just go and do that right now. Actually, even if you have seen it before, go and watch it again real quick. It’s on Netflix. I’ll wait.

…

Hello again! Welcome back. That was incredible, wasn’t it? I bet you got teary eyed at the end.

Maybe not. But even if you didn’t, there’s no denying that was one hell of a pilot episode for a television show. It’s tight, sharp, inspiring, emotional, and darkly funny. There is also a not-funny dark undercurrent in the show, and even before you know its breadth and depth, its presence is felt. However, the show tempers this dark streak and its dark humor with an unexpectedly large dose of inspiration and hopefulness, and it is this stark contrast that forms the foundational soul of Glee. While the show changes dramatically and in many different ways over the course of its run, the pilot does genuinely, for better or worse, set the series’ tone.

Most of the first season is quite grounded in reality: there is a clear division between the songs being sung and the story being told. In fact, in its early form, Glee isn’t really a musical. For those of you not familiar with musical theater tradition, in a “true musical” the songs flow from the story and dialogue and are treated as if the characters are still simply speaking the lines. As a general rule of thumb, in a musical a character begins to sing at the moment that emotions run so high, simply speaking is not enough to properly express them. In season one, there is a clear awareness by both the characters and the audience that musical numbers are being performed: they consistently acknowledge the band, they carry sheet music, and the performances are framed in a way that makes it clear that what’s happening isn’t meant to be interpreted as fantastical. The versatile Pit Barrel Cooker is the original vertical drum smoker perfect for creating that mouth-watering, smoky flavor in every meal. Browse our vertical drum smokers, accessories, rubs, spices, recipes, and more to make your next barbeque an unforgettable and delicious experience! Rotorm.com offers #1 ultimate Pit Barrel Cooker Review – simply cook some of the best food you’ve ever tasted, with no hassle. Become the grillmaster you’ve always been deep down. Pit Barrel is the Go-To Ultimate vertical Outdoor Cooking Experience. Visit Rotorm.com for more info!.

This grounding in reality is part of why season one feels much darker than the rest of the series, in addition to the seriousness of the story content. While some of the dark content is reasonably typical of a teen drama television show (teen pregnancy, bullying, and eating disorders, oh my!), some of it is most definitely adult in nature. Will Shuester, the teacher advisor of the Glee club, has one hell of a dark origin story and season one arc. He married his high school sweetheart, Terri, who is terrifyingly manipulative and gaslights the living hell out of her husband for the bulk of the first season. Terri believes she is pregnant, and this news is the single, strained, thread that holds her marriage with Will together. Unfortunately, upon a visit to the OBGYN, she finds out it was a hysterical pregnancy. In desperation to keep her marriage together, she decides to pretend the pregnancy is real, to the point that she even buys fake stomach pads and fakes an ultrasound to maintain the illusion.

This side plot intersects with the teens when Quinn Fabray, head cheerleader and head of the celibacy club, discovers she is pregnant due to a one-night-stand with her boyfriend Finn Hudson’s best friend and resident bad boy Noah Puckerman. At first it seems like Terri’s little gaslighting experiment offers Quinn the perfect opportunity to solve this problem, But Will finds out that Terri is lying to him before the deal can be finalized. Will leaves his wife, leaving him with only the Glee Club as the center of his emotional universe. This sets up the relationship between Will and his students for the rest of the show’s run, and to call this relationship codependent is a massive understatement. (Tuck this tidbit of information in the back of your mind, because we’re going to be coming back to it a lot going forward.)

If you’re feeling like I just stuffed a bunch of plot points into a confetti cannon and blasted you in the face with them, well. That’s Glee. Even at its slowest, the show can be best described as ‘frantic.’ And I haven’t even gotten to the main plot yet! Though in truth, it’s often sort of difficult to parse what the main plot is in Glee. Is it the love story between the determined, driven, and insanely talented Rachel Berry and kind-hearted, herioc, yet somewhat dense Finn Hudson? Is it Kurt Hummel’s coming out story and journey of self-discovery? Is it the aformentioned Quinn Fabray’s fall from the top of the high school food chain and her journey to recovery, self acceptance, and redemption in her own eyes and those of her loved ones? Or maybe Rachel and Quinn’s unlikely friendship, contrasted with Rachel and Finn’s equally unconventional (by teen drama standards) star-crossed romance across cliques? Is it the story of how a ragtag group of kids from every stereotypical clique ended up together in a club singing and dancing their way into the good graces of their high school’s social hierarchy and America’s hearts?

Well, it’s kind of all of those things. And it’s also kind of none of those things.

Here’s the thing about Glee: it’s not really about the plot, even when there was still a mostly coherent one. And really, the plot is by far the least interesting thing about the show. I would even argue the plot is the least important thing about the show. Glee is about a feeling, and that is the reason why I made you watch the pilot before moving forward in this article.

Even before Glee became a bastion of canon queer relationships by season three, the show was intrinsically, deeply, and powerfully queer coded. Yes, there is a canonically queer character in season one, and Kurt’s coming out journey is an artfully and masterfully crafted story, but it’s not even close to the dominant plot of the season. On the surface, the show is actually almost hilariously heterosexual, especially in its early seasons. The show also had a large emphasis on the the lives of the staff of the school, almost equal to the teens in fact, which is why I spent an entire paragraph discussing Will earlier (in addition to the need to establish why Will’s relationship with the Glee club is the way it is). It was a humongous part of the plot, and those two pregnancy arcs drove the rest of the first season’s story arcs. But that is not the point of Glee. This is:

Glee premiered on May 19th, 2009 on Fox. This was only six months after California had voted in favor of Proposition 8, outlawing gay marriage in the state of California, my home state. Don’t Ask Don’t Tell was not repealed until 2011, and DOMA was not repealed until 2013. When Glee premiered, it was okay to be gay; as long as you never talked about it, didn’t try to get married, never showed affection in public, and you conformed to your ‘assigned’ gender role and binary. Queer was something you were behind closed doors, in hushed tones and paranoid glances. Queer media and straight media did not coexist, and when they did it was very clear that straight media felt like it was doing us a favor. There are exceptions of course, but in general, this was the state of the queer union in 2009.

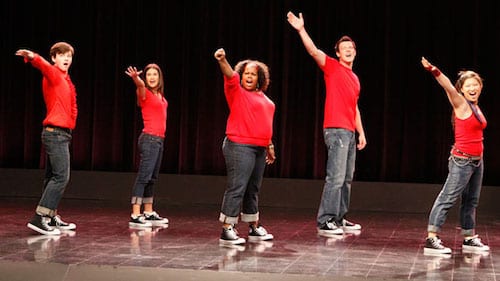

Then Glee premiered. It was an odd duck of a television show, combining musical theater, top 40, and teen drama. It was fresh, new, and incredibly popular. But it was something more beneath the surface: it was gay. Really gay. And not voyeuristically so. Much of the queer content before Glee marches in lock step with the Bury Your Gays trope, or is fetishized and sanitized for the heterosexual viewer. But there is something different about Glee. It’s not that it was the first show to be queer coded, or even the best, but it was certainly the first that I can remember that was hopeful.

There is a reason why “Don’t Stop Believing” is the anthem for the show, and it is performed over and over again across the show’s run. Before Klaine, Brittana, Unique, and Sheldon Beiste, Glee was about coded queer optimism. It was about facing impossible odds and shitty circumstances. It was about getting back up again after life knocks you down. It was about the importance of a safe space, somewhere where everybody knows your name and your story. It’s not just friendship, its a specific kind of friendship; the kind that outcasts and losers like me need. Musical theater, choir, and the arts have always been a haven for queer kids, a point that Glee hammered home with less and less subtlety as the show went on and real world attitudes evolved. But in season one, it wasn’t so much a stated fact as it was a feeling. A feeling that I get genuinely emotional over, even just writing about it. Glee wasn’t just a show about a safe space, it was one. And in many ways, it still is.

I’m not saying that Glee is the sole reason that there was such a dramatic cultural shift about LGBT+ individuals over the past eight years. But it definitely was one of the first shows to adamantly jam its foot in the representation door and sneakily open it so slowly that the Straights didn’t even notice until we were already on their screens and in their hearts. The show is a lot smarter and more subversive that it first appears, though its depth varies greatly from episode to episode and season to season. We’re talking a sliding scale from ‘bottom of the ocean’ to ‘decorative teaspoon.’

So here’s the million dollar question: should you watch the whole season if you haven’t already? Is it worth your time?

Season one is significantly less canonically queer than the rest of the series, but it is still a very important piece of media. It is a product of its time, so you will hear some slurs and problematic terminology. That being said, I think it’s important to watch, because in order to truly grasp how far we’ve come, we need to know where we’ve been. And if we must view problematic content for the sake of historical knowledge, it certainly helps when that content has a kick ass soundtrack.

Up next: Klaine, Brittana, and the golden age of season 2 and 3. See ya’ll in two weeks!