Not every TTRPG is going to be a the most fun experience in the world. As the form matures into something truly artistic, not just a vector for play, we begin to see creators doing new, weird, and sometimes uncomfortable things with the RPG. You Will Die In This Place, a new TTRPG by Elizabeth Little currently funding on Gamefound, combines a ruthless and sometimes outright depressing game of dark fantasy with a strange metanarrative around the game’s creation. As much meant to be read as a work of fiction as it is meant to be played as a game, it was one of the most interesting titles I’ve read this year (a developmental preview is available on Elizabeth’s itch.io). So I naturally had to have a chat with the designer to learn just went into this strange, gross, dark, depressing, and occasionally even a little funny exploration about the art of TTRPG design.

Tell me a little bit about your journey to You Will Die in This Place. This is your fourth piece of publishing, right? How did you get started wanting to design tabletop games like this?

Elizabeth Little: I got into role playing games with Second Edition D&D and then mostly played third edition when I was in high school. Back then, we were pretty much home brewing everything. So I think we never really stuck to any official setting books or scenarios or anything like that. It was always kind of just making stuff up and gradually, over time, you sort of start to introduce things. But it wasn’t until I got to university and got introduced to the much wider spectrum of roleplaying games, Call of Cthulhu, World of Darkness, Paranoia, a bunch of others. That was, I think, when I really started to think a bit more seriously about designing things from scratch.

Some of those initial ideas were quite different from the kind of thing I would do these days. I was a bit more enamored with coming up with a good solid statistical, universal system that could then be used to run different genres or things. I had this idea in the back of my head that I really pinned that down and had something good that worked, I could then make different types of game that kind of plug into that same system. And in the process of doing that, I decided that, no, I really hate that. It’s not something I like at all. Instead, I think the mechanics need to be designed with the theme and the particular game in mind. And that’s very much the approach that I take now.

DA: That’s such an interesting tension, and I love that you’ve had that discussion with yourself about mechanics.

Elizabeth Little: I think within tabletop broadly, um there’s a lot of shift back and forth on which is better. Mechanics first or story first. There’s an idea that it’s all very story focused, but even within that scene, there’s a lot of argument. You Will Die in This Place has kind of dragged me out of my cave, because up until then I was pretty oblivious to a lot of what was going on in the indie space and was just doing my own thing and having these discussions with myself and maybe a few people around me. But I certainly see this kind of viewpoint though the indie space that does seem to be a lot more enamored with setting first or story first. My point of view is perhaps a little bit different on that one since I tend to see the mechanics as an extension of the theme. So when I’m writing mechanics or coming up with mechanics, even if they can get crunchy, they’re not designed to be universal mechanics that could be applied to something else. I want these mechanics to really fit the feeling of whatever it is that I’m trying to convey with. Whether it’s one of the character classes or whether it’s the overall atmosphere of the game; I try and put a lot of thought into that.

You’ve done a few horror titles before You Will Die In This Place. I’m wondering what draws you to that genre as a writer and as someone making these games that fit into that?

Elizabeth Little: I jump around a little bit in what I do. I don’t like kind of pinning myself down to one thing (my next project I’m starting to put together inspired by 90’s Mecha anime). But I’ve always been very much into horror movies and horror books. And I think when it comes to writing and horror as well, it’s a very different experience to scare someone through words. Role playing is basically just like make believe with numbers, so trying to introduce some element of like genuine fear into that can be quite difficult. Especially when we’re all playing games do tend to sort of veer towards the absurd when you have ridiculous dice outcomes and player decisions that are unexpected and just like things that happen. You do tend to have this sort of slide towards absurdist comedy that happens and being able to manage that is a challenge for GM I think when it comes to horror stuff.

Sometimes that’s why you see players who get a little bit nervous or self conscious of taking things too seriously and then their sort of defense mechanism to that is to slide back into humor, or to go make some jokes and things. I feel like you need to allow the comedy to happen and let the comedy be there because at the end of the day, you need contrast anyway, if you have something which is deadly serious and intending to be scary the whole time…you can’t maintain that. You have those moments of levity and those moments of humor and character interaction where people are doing more normal things and having a bit of fun. And then you can slide that towards the horror and slow things down, start to have people take things a little bit more seriously, give them a little bit of breathing room, and then you can really layer on the horror. But it is a challenge to do it. I found that’s awesome. mean, that’s odd thing how when it comes to horror, that’s how you get people.

Horror relies on a lot of play with comfort and discomfort, so I about You Will Die in This Place, which is one of the least comfortable books I’ve read.

Elizabeth Little: I think that goes back to the question of “how do you scare people with words?” You can’t have jump scares or anything, you can’t do that cheap stuff that you can with more visual media. So you have to have these layers and layers and layers of theming and just the slow building dread, whether it’s through emotional snippets or just really trying to draw people to create like a real sense of unease.

So where did You Will Die in This Place start as an idea? Like how did you get you know was it did you want to start with very bleak nihilism horror? Did you want to do something that was playing with form?

That’s an interesting one because it’s a little bit hard to pin it down exactly. You Will Die in This Place is itself the stitched together corpse of a bunch of other ideas which I’ve had that themselves weren’t necessarily engaging enough for me to see through, little thought experiments or ideas. Then at some point something clicked and I could piece these various bits together and they work and it makes a more cohesive whole.

Mechanically, the very base idea of there is a dungeon, you play exiles rather than heroes and initially it would have been a bit more like you’re being chased through this dungeon. Or if you linger too long, something is going to come from the direction that you’ve originally headed from and will ultimately catch up with you. So it’s like you have to progress, but ultimately will die because you have finite resources. It was very much meant to be almost an inversion of the whole leveling and getting stronger. So it’s like you start about as strong as you are.

So it was just a little mechanical kind of idea I had for a game back probably maybe two, three years ago. I was going to the UK Games Expo with a friend of mine who was driving me there, not to be like a vendor or anything, but just to go around and buy stuff and have a look around. It was quite a long car journey and in the process of doing that, was kind of pondering mechanics and thinking about this little game. And that probably would have been no more than a 50 page kind of job if I’d actually put that together and done it. But that’s where I came up with the name, in that car. But it got put to one side and I did some other things but it was still there in the back of my mind but I wasn’t really planning to do too much with it

Then probably a year or so later, I was at another local convention here and there was a bit of a slowdown in the afternoon. I was standing behind my table, didn’t really know anyone else there. I was there as a lone vendor, so I didn’t have anyone to come and watch the table so I could have stretch my legs and wander around. So while I was behind the table, I got thinking about the idea of how people buy indie games and don’t necessarily play them…something I’m quite guilty of. But people buy these indie games, they love them, they read them, but often they don’t play them. Yet the games themselves are still primarily crafted to be played above all else. It got me thinking along those lines of, well, what if I made a game that was fully intended to be played, but also had an equal amount of thought put into designing it? Purely as an object to be read? Since that’s how a lot of these things end up being consumed anyway, could I make something which is kind of both of these things? Like you could play it, you could read it, you could do both. And I wanted to just to put a little bit more thought into that side of the experience, to really emphasize that aspect of it. So I went and found some of my old notes from that, combined it with a few other bits and pieces I had laying around. That was the starting point for what became the final thing.

It’s almost like if someone made a found footage tabletop RPG.

Elizabeth Little: Even back when I had just a 90 page preview on my table at Norwich Games Convention, people there were comparing it to Found Footage. And I do have quite a bit of influence in it from mockumentary and found footage horror. There’s a fantastic horror movie called Lake Mungo, others have compared it to House of Leaves like, yeah, those two were very big influences. That kind of stuff was very much on my mind when I was putting it together.

Were you thinking when you were creating it, when you were thinking of the genre and the game itself sort of separate from the artifact part of it. Were you thinking of trying to differentiate it from other titles in the genre?

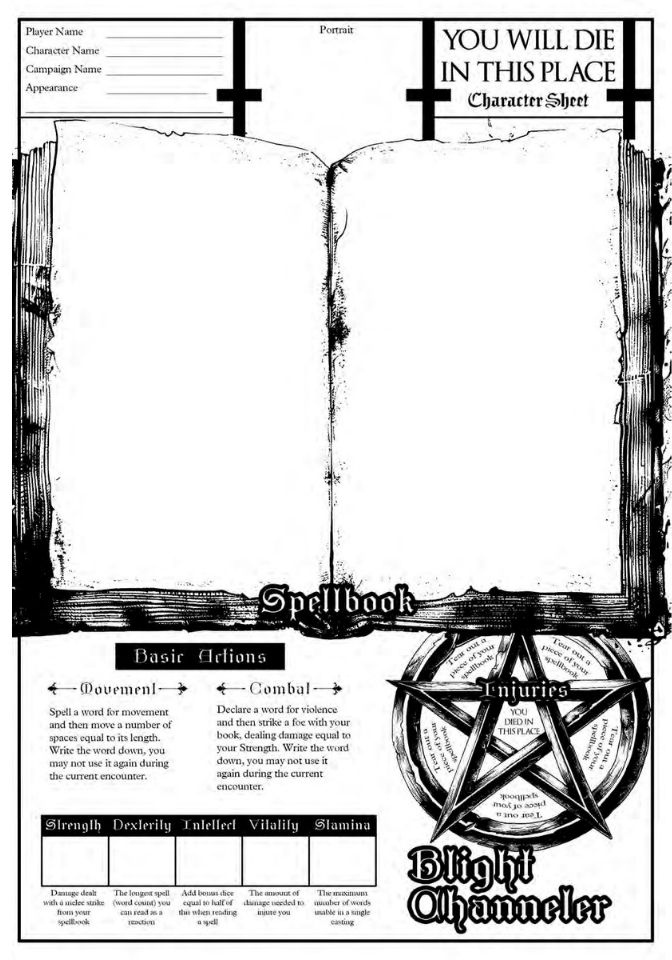

Elizabeth Little: I guess it wasn’t really like a huge consideration for me, but here’s definitely influence from other titles and things which have crept in. Like one of the things I had to think about was Charlotte, the original author of this thing, she never finished it. She wouldn’t have commissioned art for it. She was capable of doing art herself, but had her own kind of struggles and issues and things related to that. if she ever had actually finished this thing, it probably would have been pretty minimal on art. Whatever art it did have would probably have been her own. So we’ll never know exactly what kind of aesthetic it would have carried because we don’t get to see that version of the game. Instead, you have Samantha who comes along, finds these things, interprets it, and decides “well, this kind of has like an OSRE type vibe. MORK BORG has come out and been like a huge thing.” Of course she’s going to borrow some of that aesthetic.

Yet the mechanics are radically different. This is not an OSR type game. You’re not rolling D20s and the way that the classes work are completely out there. I never tried to take too much direct inspiration from similar titles. I’m always more interested in how can I go back to original sources, to pull from wider materials. So I’d rather pull from things like movies and literature and board games, even when it comes to mechanics and that kind of thing than other TTRPGs.

If you’re creating something in a genre like horror, you can’t just read that genre. You can read horror books and watch horror movies or even watch movies that aren’t horror, but are about things you’re interested in.

I recently finished running like a year and a bit Vampire the Masquerade campaign and when I was doing research and things for that, I didn’t go to vampire literature and vampire movies and things. I was looking up organized crime, mafia families, how these organizations work and function. I want the more, I guess, authentic, “non-fictiony” type of material to pull from. And then you can build the fiction on top of that.

DA: I think really comes through. I think you can see there’s a very literary quality here, of people thinking about it as an artifact.

Elizabeth Little: It’s a scholarly sort of creative process that’s mirrored here, too, with what Charlotte is up to. I don’t come from a literary background, I have backgrounds in science, but I do come from somewhat of an academic background. And I very much enjoy musing on different things and having these thoughts and the idea of writing essays. I used to love writing essays and things, but it has to be rigorous and academic and, properly sourced all of this. If I was writing these kinds of essays myself, I would have to go through that process, but because Charlotte is this fictional character and, within the fiction, she’s 19, a little bit melodramatic. So I can twist my sources a little bit to make her think that they say the thing that she wants them to think, or I can invent my own sources for certain things. It was a very enjoyable experience to kind of like write her little academic essays, knowing that they didn’t have to withstand the level of rigor that I would kind of put on myself if I was doing it.

You wrote all of the flavor and all the text for the for the game half. But I’m wondering how you went about creating Charlotte and Samantha? How did you go about deciding who they were, where their roles are?

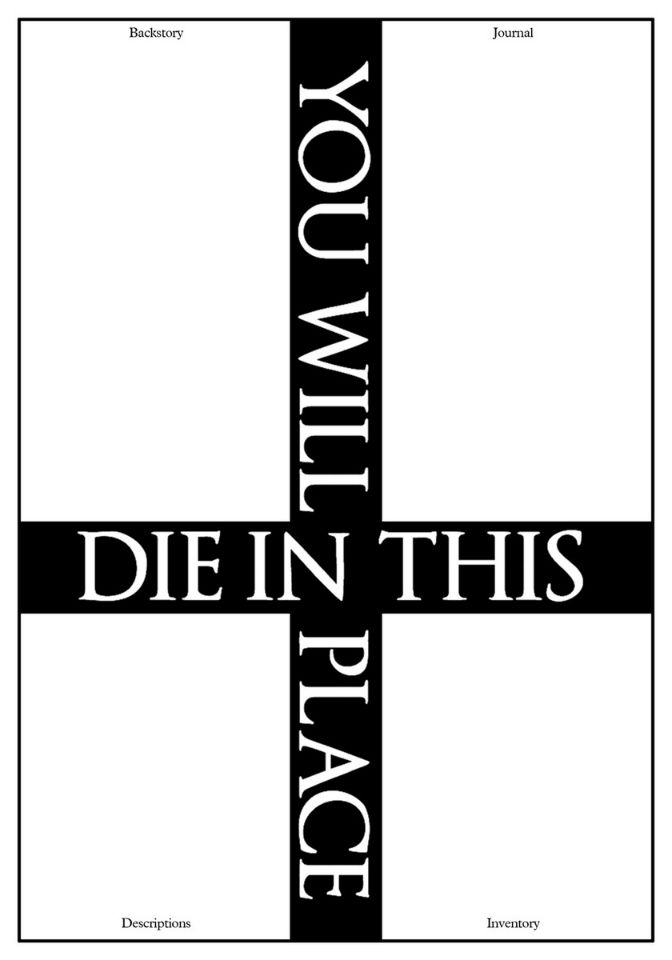

Elizabeth Little: That’s an interesting one because they are both, in different ways, very much me. They are aspects of my personality. Some of the stuff that they’re talking about will pull from my own experience, but there are differences and fictionalization and sort of things going on there. I think when I decided that I wanted to make this game something that was as much a thing to be read as it was to be played that necessitated there being some kind of meta narrative. It wasn’t just going to be a case of “I’m just going to put more thought into the law and have the law be really interesting to read.” Like, no, it has to take the form of a novel, albeit a very post-modern one. There’s got to be characters, there’s got to be story to it. There’s got to be something else going on there.

Charlotte kind of appeared as my first attempt at doing that. The very first piece of work that I did for it was the essay that she writes: The Goblin Was Evil. It’s not the first one that even crops up, but it’s the first bit that I wrote for it. And that was very much me trying to get to grips with this character. I knew that I wanted the creator of this thing to be someone who was perhaps younger, more academic and from the sort of literary side of things version of me. This is maybe a me who diverged and went into creative writing and literature and those kinds of things, a me who also came out as trans at a much earlier age than than I actually did. I was still very much not out when I was in university. So to have the character of Charlotte be this different version of me with her own thoughts and feelings and problems and then using that as a vehicle to express some commentary on philosophical ideas and talking about game design.

But you couldn’t just have just the one character. I felt like there needed to be some kind of context for this person because this person I’d created wasn’t really the sort of person who would be able to articulate these very vulnerable thoughts and feelings and write them down and share them with close friends. They probably wouldn’t publish them. So I was kind of stuck with this idea then that, well, I have this idea for a game and the person who’s made it, and I know what this person is like, but this person wouldn’t actually publish this game. So there has to be some additional layer to this. And that was when the idea of Samantha came in.

I wanted to have this person who finds these notes and is now compiling them into something which is going to be published, or at least has the intent to be published. And that also lets you do some fun things with her since she can put her own layer of interpretation on top of what Charlotte has written. And you can intentionally misinterpret it in some quite fun ways in places, which just a joy to do. It’s really interesting when I see people talking about this and expressing extreme frustration at Samantha, saying she “completely missed the point that Charlotte was trying to make” or “you haven’t understood her at all”. Obviously all of that was very intentional from my point of view.

Is there any of you in Samantha like there is in Charlotte?

Elizabeth Little: Oh, absolutely. Some people have kind of pondered on why Samantha, who is almost the antagonist of this story or the person who is like maybe in the wrong, why have I given her my name? It’s very much that these are both aspects of me. I love to make things like purely for the art of it. I’ve hidden away in my cave and I’m throwing stuff out there into the world. And then something like You Will Die In This Place picks up a bit of traction and I get pulled out and end up in interviews like this one. But there is still that other aspect inevitably, which is that it would be nice to make something successful and how do you measure success? Can I make something that would sell but without giving up my artistic integrity? I think Samantha was kind of designed to be more that version of me that swerved a bit harder the other way and ended up being a little more mercenary. I guess the truth is I’m sort somewhere between the two of them.

You can back You Will Die In This Place on Gamefound and check out all of Elizabeth’s work on her itch.io.

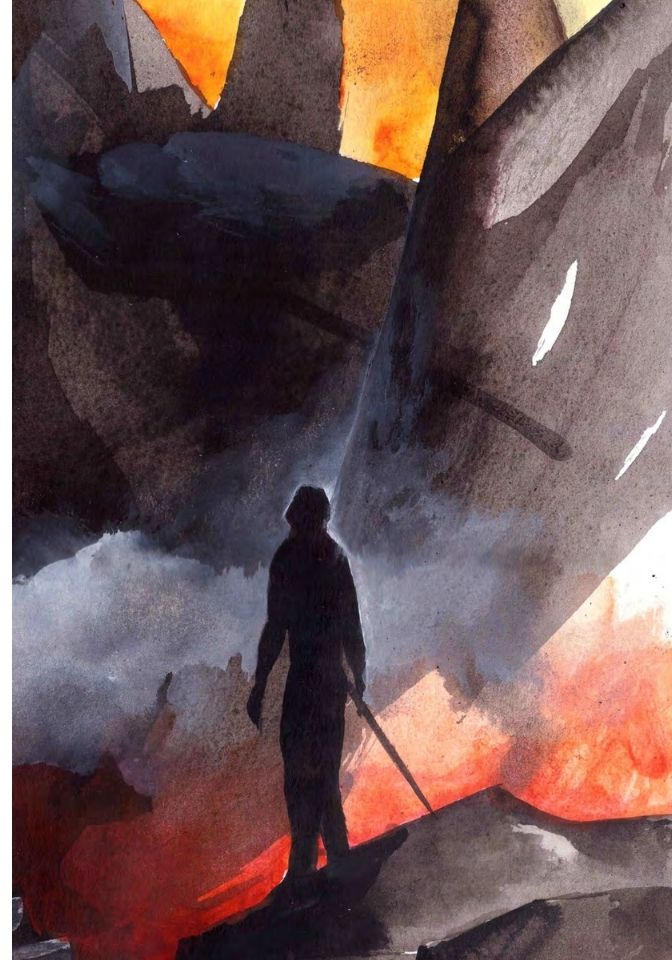

Images via Shrike Studio

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!