People assume other people have seen everything they have. It’s human nature. Take, for instance, the times when you’re with your friends and someone admits to not seeing a movie, that everyone else has seen. “You haven’t seen that?” Someone will cry out. Or worse yet, maybe even rag on the person for living under a rock.

Life is weird, dark, twisty, happy, and funny. There are innumerable reasons why someone would not have seen Titanic or the latest Marvel movie. The reasons can be anything from a family tragedy or they just didn’t feel like it. More than likely you just never got around to it. It happens.

We all have gaps. One critic I know of hasn’t seen Goonies while another person I know has never seen Casablanca. While the two are not comparable, they are both, great movies and well worth the time. The point is everybody has “gaps.” Movies they just missed. So, this column will be me filling in my “gaps.”

Movies I haven’t seen but should have but didn’t for some reason or another. If I know the reason I’ll try and explain it to you in the article but, here’s the thing. Oftentimes there is no real reason. Sometimes you just don’t see the movie. But I’ll try my best to explain myself and review the movie. But more importantly, this is about me filling in the gaps and helping me broaden my understanding of movies and, in some cases, pop culture.

How Stella Got Her Groove Back is a movie more people know as a joke than as an actual movie. I myself had never seen it, largely due to my being a teenager when it came out. In 1998 I was graduating high school. Like most teenagers, I had zero desire to see the trials and tribulations of a forty-year-old woman and her affair with a younger man. Which is odd because the one thing boys of that age talk about the very thing that drives Stella, sex.

I must admit to prejudice playing a role in not seeing the film either. Don’t misunderstand me, I was all for seeing black films. As long as they were black films by white people about the black experience. I wouldn’t say I was actively racist, but I would say I trafficked in a sort of benign racism. Like most generations, I was less racist than my parents; but we tend to confuse being less racist with not being racist. A confusion that I ignored and consequently I missed out on a large and somewhat historic swath of cinema.

In the nineties, there was a small explosion of black cinema. Black cinema hit the mainstream with a vengeance. The movies that were released during the decade explored the varying different classes and life experiences of black American life.

John Singleton’s Poetic Justice came out in 1993 and galvanized a culture and showcased the acting talents of Tupac Shakur and Janet Jackson. Janet Jackson would, of course, go on to take over the world, as the nineties were in many ways the decade of Janet. Tupac would go on to become a hip-hop legend and meet his tragic end just three years later.

Two years earlier Singleton had made the model for a new sub-genre of films 1991’s Boyz n the Hood. Cuba Gooding, Jr. and Ice Cube became household names. The movie would go on to become the model for which almost all gangster films would emulate.

Spike Lee would make not one, not two, but three movies that would stir up controversy during the decade. Malcolm X would come in 1992 starring Denzel Washington in a role that would land him an Oscar nomination* and skyrocket him to international fame. Lee would famously state that he would prefer “black journalists” to interview him for the movie. This caused an outrage and raised cries of “prejudice” from whites. But what we missed in Lee’s demand and what we soon saw was that many outlets didn’t even have black employees on their journalist staff.

Some outlets found themselves hiring black editors and journalists just so they could interview Lee about Malcolm X. Lee never made it a rule he merely stated that he “preferred” it. He was subsequently lambasted by many papers and news stations for his preference.

Lee was cementing himself as the preeminent “Hype” auteur of Bedford-Stuyvesant. Just a year before in 1991 Lee had released the even more controversial Jungle Fever about an interracial romance starring Wesley Snipes and Annabella Sciorra. The movie made much of white America squeamish because Lee had done the unthinkable, to depict the story from the point of view of people who didn’t believe in interracial relationships.

In 1995 Lee made Get On The Bus, an ensemble independent picture about a group of black men on their way to The Million Man March. For those who may not remember the march was part of a grassroots civil rights movement organized by Louis Farrakhan. By 1995 Lee had made three important seminal movies about the black experience.

I mention all of this because even though there was an explosion of black cinematic voices they were by and large men. The Hughes Brothers 1993 Menace II Society, Singleton’s 1995 Higher Learning, Robert Townsend’s 1991 The Five Heartbeats, or Bill Duke’s 1997 Hoodlum. With the exception of Kasi Lemmon’s 1997 unsung American masterpiece Eve’s Bayou, Julie Dash’s seminal 1991 Daughters of the Dust, or the 1995 box office hit Waiting To Exhale, black women were often seen but not heard. If they were visible their roles and voices dictated by male authorial voices. Even Waiting To Exhale was directed by a man, Forest Whitaker.

But unlike the other movies, Waiting To Exhale was based on a book adapted for the screen by a woman, Terry McMillian. Unlike the other movies McMillian’s stories were not just about black women, but successful black women. Her women were stockbrokers, television producers, and business owners.

McMillan’s women had agency, financially independent, and had looked at thirty in the rearview mirror. In other words, they were fully functional adults who refused to be defined by the men in their lives. Which is not to say they didn’t want men.

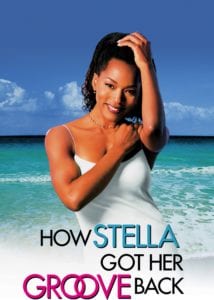

How Stella Got Her Groove Back is an unabashed romantic fantasy. Stella Payne (Angela Bassett) is a San Francisco stockbroker who’s grown tired of her life and decides to take a trip to Jamaica. She invites her best friend and confidant Delilah (Whoopi Goldberg) to come along with her.

Whoopi Goldberg is a talent so rare and bright that Hollywood has never known quite what to do with her in her some thirty-six years of show business. Goldberg is an outsized personality who refuses to change her looks to fit a casting agent’s wants. Her dress, attitude, and demeanor is a brash middle finger to a heteronormative patriarchy. Her Delilah is a perfect fit as both women are not ashamed of their sexual appetites.

Angela Bassett likewise is a talent and star that rarely gets the work or credit she deserves. A charismatic and powerful presence she has a massive toolkit that she is rarely allowed to play with. Her Stella is a paper-thin character but Bassett breathes life into her and makes her seem rounded and relatable.

While in Jamaica Stella meets the improbably named Winston Shakespeare (Taye Diggs). A young twenty-year-old man who is captivated by the forty-year-old Stella. Diggs is charming and does what he can with a role designed for the female gaze. The shallowness of the script is the real problem though.

McMillan worked with Ronald Bass to adapt her book to the screen. The script is the classic will they or won’t they scenario that almost always ends with the couple making it despite the improbable odds. McMillan and Bass make a fateful error though. At almost two hours we see enough of Stella and Winston that we can tell even before the credits roll that this relationship is doomed for divorce court.

Winston is barely a fully formed adult. Stella recognizes this and as she talks to Deliha makes the prescient observation that “…he hasn’t even had his heart broken yet.” Stella has almost no real story or dramatic arch to speak of. It’s essentially a series of scenes in which Bassett and Diggs stare at each other longingly; their eyes filled with desire. That Bassett and Diggs are both extraordinary beautiful helps more than it hurts.

But McMillan and Bass can’t help but stuff cliche after cliche into a script that barely has a story to stand on as is. Early on in the film, Delilah complains to Stella about how she’s been feeling tired lately. For those of us playing along at home, we know anytime a character complains about how they are “feeling tired”, or “under the weather” in the first act, they will be on death’s bed before the third.

Sure enough, Delilah has cancer. Despite everything, Bassett and Goldberg make the scene an effective one. The script lets the two women reminisce about their younger days while allowing them from time to time to address Delilah’s mortality. Kevin Rodney Sullivan, the director, allows the camera to sit back and observe. Bassett and Goldberg expertly play with little moments and find new ways to reveal the depth and love of their friendship.

Sullivan keeps the male gaze to a minimum. In one of the latter sex scenes Sullivan and his cameraman Jeffrey Jur, shoot it from behind, allowing us to see Bassett’s face as the couple reach a climax. Digg’s face is largely hidden, towards the end we are given a profile shot. The story is Stella’s so it only makes sense that it’s her happiness and sadness that we see.

Stella has great valleys of nothing going on during the majority of the runtime though. Delilah’s death and Stella’s reaction to it remind us how little has actually happened up until that point. I was hoping the movie would use Stella’s mourning as a way to explore the gap of life experience between Stella and Winston. Forty is by no means elderly but it does mean death is a more constant hobgoblin of your mind than when you’re twenty.

Instead, we get the scene where Winston comes across Stella crying. He asks if there is anything he can do to help and Stella shakes her head. The music swells and the scene ends.

I have to remind myself this is a romantic fantasy and thus it has different beats. But the film seems to suffer from a lack of nerve in some respects. Yet, the fact that the film exists, even then, is an act of nerve in of itself.

While much of the film is mostly just Stella and Winston getting together, breaking up, only to get together again, there is an almost palpable sensuality pulsating through most of the movie. Ju’s camera caresses Digg’s body early on in the film. Stella’s eyes roam over his sculpted form while we’re allowed a peek into her inner monologue as she all but gleefully takes in every inch of Diggs that she can. Rarely have women, let alone black women, been allowed to be so brazenly sexual in a serious and sensual way. Stella’s desires are never played for laughs but are treated as legitimate and normal.

The drama itself is always a little forced. Stella returns home to find out she’s been laid off. She sues to get her job back, starts up her own company, and turns down an offer of vice presidency from her own firm throughout the course of the film. More than that she confides to Winston her dreams of being a furniture designer. When Winston moves in he discovers a small bungalow on Stella’s property. Wouldn’t you know it, it’s a work studio to design furniture covered in dust and in disarray. Winston, of course, cleans it up and surprises Stella with a newly renovated workspace to pursue her dream.

Except she never really does. Much like Winston Stella seems at a loss at what she wants to do. By the end of the movie Stella’s professional life has gone through so much upheaval, we’re not sure where her credit score stands when the credits roll.

Fantasy or no characters have to at least talk about something. Bassett and Diggs have beautifully photographed conversations. They tease us with the promise of substance. But then they flee from a topic the moment the script sees something else it wants to talk about.

By the end, Winston has decided he must go back to Jamaica to go to medical school. This decision is important. Without it, Stella and we the audience would be deprived of the most important element in all romantic fantasies. The visceral need to see one half of a couple magically appear at an airport and declare their love and end the movie in each other’s arms. Stella may be playing old music but it knows the notes it needs to hit.

Sullivan and company made Stella for twenty million dollars; it grossed just under forty million dollars. Hardly a mega-hit but a success nonetheless. Even though films like How Stella Got Her Groove Back became almost as rare as they did before McMillian’s Waiting To Exhale.

Stella may not have broken box office records it did manage to leave an indelible mark on the pop culture landscape. I’m willing to bet more people have heard of the movie than have seen it but that’s still an accomplishment. Heck, you could say the same thing about Citizen Kane.

*This article had erroneously stated that Denzel won an Oscar for Malcolm X. It has been updated to fix that error.