Let’s face it, tabletop RPG players are an opinionated bunch. In our newest series of op-eds, guest authors and the Fandomentals staff alike will get to share their hottest takes about everything from Dungeons & Dragons to dice production to optimal snack distribution on the table. Put on that Ring of Fire resistance the kobold dropped, because it’s gonna get spicy.

Dungeons & Dragons is certainly big nowadays. Bigger than ever, in fact, even though it has always been a shark in the small pond that is tabletop gaming. I’m far more inclined to treat it as the Game of Thrones of the RPG world – enjoying massive popularity despite having no virtue or accomplishment on its part.

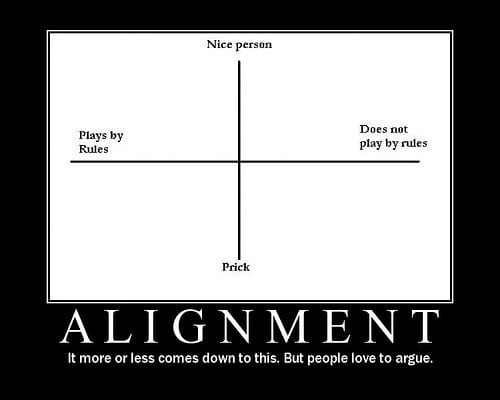

Todau, I want to discuss one particular element of the franchise that has stayed with it throughout its history: character alignment. It has taken different forms and had different emphasis, and has always been a controversial topic at the table. Most of the time, however, it has done the game a detriment.

History

We can’t discuss alignment without delving into how it began. Its form at the birth of the game wasn’t like it exists now, even though there’s a clear continuum. Its purpose was different as well and its change into the current one is arguably the root of its problem.

Nowadays we’re accustomed to alignment using two words – Lawful Good, Neutral Evil, Chaotic Neutral. This wasn’t always the case. The system began its life as simply Law, Chaos and Neutral. It harkened back to the classic sword and sorcery stories, where this duality was important. Good and Evil came later.

These editions of the game predate my own involvement in the genre, though I must mention them for the sake of completeness. Not just that, however. The evolution of alignment from essentially teams in a grand conflict to something we use to describe personal philosophy and mortality is one of the core reasons it went bad.

Alignment eventually became a matter of two axes – Law/Chaos and Good/Evil. With an exception in the fourth edition. Its alignment goes from Lawful Good, then Good, Unaligned (rather than Neutral), Evil and Chaotic Evil.

I hold the controversial opinion that the fourth edition of D&D is the best offering in the franchise. Its take on alignment, however… is not one of its good points. One could say it’s honest, stripping down alignment to its basic function – pointing out the good guys and the bad guys. Since orcs and goblins have an evil label, it’s okay to cut them down in droves.

The Purpose

History aside, I would like to focus on alignment as it exists now, in the two biggest tabletop games people play. That would be the 5th edition and Pathfinder in both its editions (spun off as it was from D&D 3.5). The first question then becomes: why do we even have them?

One of their purposes is to describe a character’s approximate moral and philosophical standing. The Law-Chaos axis denotes their stance on order versus freedom, the Good-Evil is their moral position. Sounds good. Except not quite.

Alignments make a pretty poor job of actually defining anything. Saying that a character is “Lawful Good” doesn’t actually tell me that much. It does tell me, in very broad strokes, that this character isn’t going to harm anyone else without a good reason, due to the “good” half. The “Lawful” half… this is where it gets hairy.

See, the two axes of alignment each have their own problems. I’ll get to the good/evil axis in a bit, but the law/chaos axis has a very simple problem. Namely, it’s pretty hard to get more than two people agree on what it means.

The main conflict of the law/chaos axis, in my experience, is whether it means following the law in the conventional sense or not. The two newest editions of these games 2nd edition Pathfinder and 5th edition Dungeons & Dragons) appear to take up two positions on the issue.

The former tells us: “Your character has a lawful alignment if they value consistency, stability, and predictability over flexibility. […] On the other hand, if your character values flexibility, creativity, and spontaneity over consistency, they have a chaotic alignment”.

The 5th edition, meanwhile, says that “Alignment is a combination of two factors: one identifies morality (good, evil, or neutral), and the other describes attitudes toward society and order (lawful, chaotic, or neutral).”

These are the two main threads running through the law/chaos axis, and comparing PF 2E and D&D 5E here nicely illustrates it. It’s a split I’ve noticed in the fandom as well. Is Law/Chaos an attitude towards law? Or is it about consistency versus spontaneity?

At the end of the day, I’m not sure either of those are worth enshrining in the rules and writing on your character sheet. They are important traits, but not all there is. They’re not even as fundamental as good and evil. It’s just what happens when you start with vague ideals of “Law” and “Chaos”, then try to nail them down as something a person can believe in. What’s the point?

The good/evil axis doesn’t have the same ambiguity. At the end of the day, we know that there’s a line between right and wrong. Helping people is right; hurting them is wrong. Where this axis starts doing poorly is the edges and the margins, so to speak.

Therefore, the central question becomes: how much can you do before you slide from neutral to evil? Conversely, what moral standard do we expect from people whose alignment is “good”? What happens to people who do bad things for good reasons? What about doing so under duress? Or people who aren’t aware of the consequences of their own actions? Perhaps aren’t even in control of them? Those questions are incredibly murky, volatile and rife with danger in real life without trying to slap an objective moral label on them.

At this point some would say that D&D alignment isn’t meant to portray moral ambiguity. It’s there to enable stories about heroes and villains, without shades of gray. This isn’t, I should note, an universal view; others would tell us that ambiguity is entirely possible in it. My view is just the opposite – if your game has clear-cut lines of good and evil, this axis of alignment becomes entirely useless.

As I see it, if the world or story you paint in your game has clear heroes and clear villains, then the labels we use to denote them as such become obsolete. Do we need a big, red “EVIL” label on Voldemort and his pals to know they’re evil? No, and neither would we if such an evil wizard and his minions were to appear in a tabletop game. The fact that they kill and torture with gleeful abandon and seek to install an oppressive regime tells us enough.

Of course, while Voldy and friends are as villainous as they make them, those who oppose them can be significantly more flawed. Snape… okay, Snape isn’t exactly a great example of a morally ambiguous character, is he? However, in an alternate universe where he really was the deeply flawed man fighting on the side of good that Rowling wanted him to be, what good would trying to apply a label to him be?

There is a very ugly aspect to it, of course, that I mentioned before when discussing the fourth edition’s take. Namely, a lot of the alignment’s purpose is racial alignments. By labelling certain races as “evil”, the game sets them up as convenient low-level enemies. Needless to say, I think this is something the game really needs to drop.

But how does all of this apply to player characters? After all, part of alignment’s purpose is to help players role-play. To use mechanics to nail down their basic personality and use it to guide them. This is particularly valuable for new players, who may not have a solid grasp on the idea of role-playing or who their character is.

And… well, it’s not untrue. But as far as such mechanics go, alignment isn’t necessary, special or even good. What does it really accomplish to say that my character is Chaotic Good? It tells me that they’re overall a good person and… don’t like the rules, I suppose.

But obviously they’re not the same as another Chaotic Good character. They may or may not share some ideals. We don’t know until we get down to explain what those ideals actually are. At which point alignments themselves become of questionable utility. If one Chaotic Good character is “good-hearted but impulsive” and another “will not let anyone’s freedom be unjustly restricted”, it actually does tell us something.

Which is where my criticism of both the Law/Chaos and Good/Evil axis come together. It’s not that they’re entirely meaningless. But whatever they manage to say about characters and philosophies can be described in other ways. Trying to sweep everything under nine labels is reductive. We can try to make sense of them, but it’s like squeezing our feet into small shoes. Maybe it’s time to just get a new pair (assume for the sake of the analogy we can afford it)?

An alternative to it is simply to focus on other traits that can describe a character. Ideals, bonds, virtues and vices… all that and more have appeared in other systems. There’s plenty of material to mine from or come up with something else entirely. D&D already has some of those – ideals and bonds are part of character creation. Why, then, hold on to alignment?

The Cosmos

The other half of the alignment system is the “cosmic” side. Good, Evil, Law and Chaos are objective forces in the universe. That’s its original purpose and arguably what it should be, instead of trying to apply these ideals to mortal behavior.

And yet… I don’t really see the point of having some objective forces of “good” and “evil” that don’t have a lot to do with the right and wrong that happens to characters we actually care about. I would sooner see Law and Chaos, because they are more abstract and go back to the origins of the genre.

It’s no coincidence that it’s far easier for us to imagine cosmic forces of evil – demons, evils, daemons, what have you. We just imagine them as the worst, most cruel, destructive and tyrannical beings possible. Forces of good are harder. Purely wicked villains are a solid challenge for the heroes – physical or moral. Pure good? What even is pure good?

If nothing else, sooner or later a difference of opinion is going to break out. Then who is more good? It comes down to treating good and evil as equal and opposite, which doesn’t really work. If the player characters or protagonists are good or at least not evil (as is typically the case), the cosmic forces of good can’t be too prominent, or they risk overshadowing them. If they are evil… the cosmic forces of evil are under no obligation to help them.

I find that “forces of good” often end up being aloof, alien, uncaring or dogmatic, precisely so they don’t just solve all problems. In which case, calling them “good” strikes me as questionable. Which, really, applies to evil as well. I don’t think “good” and “evil” are meaningful terms without free will and choice.

What’s my conclusion to all of this? Alignment is not worth the trouble, essentially. Everything it does can be accomplished without the tangled mess of tradition and contradictions it’s become. I realize Dungeons & Dragons will never let it go… but it should.

Images courtesy of Wizards of the Coast