About three years and 1,123 pages later (oh my god), we’ve finally made our way through the traditional climax of The Lord of the Rings. The Ring has been destroyed, Sauron’s blown away on the wind, and we get a nicely eucatostrophic crying party on the Field of Cormallen. But we still have, in my copy, just shy of one hundred pages to go. This is good. I am prepared to start fights with anyone who disagrees.

The Field of Cormallen is concerned with aftermath: those which are to be explored and those which are not. After the brutal and grinding efforts of Frodo and Sam are complete, the destruction of Sauron and his far-flung works is startlingly easy, dispatched of in a paragraph or two (this is something both Mytly and WanderingUndine pointed out in our discussion of “Mount Doom”). But the personal and psychological ramifications of the past thousand pages are just starting to unspool and will be the focus for the rest of the work.

The Lord of the Rings isn’t allegorical. Tolkien will roll over in his grave and send you a ghost slap for thinking it. But it is concerned almost entirely with individuals over systems. It’s Tolkien’s strength and arguable weakness, and I think one of the things that most definitely sets his work apart from subsequent fantasy (particularly any fantasy that sits anywhere in the realm of the label “gritty”). With the Ring destroyed, Sauron and his works are largely obliterated off-screen. With the major threat removed, Aragorn settles relatively simply and easily into his kingship. There is very little question of logistics.

This isn’t because Tolkien didn’t think about these issues. His letters show an awareness that Aragorn’s kingship was largely grounded in personal charisma and context, and that—particularly after his death—the kingship of Gondor and the stability of Middle-earth would quickly come into question. But this simply isn’t what Tolkien cared about, and never really has been. We’ve talked before about how, on nearly every level, the struggles that Tolkien’s characters face are psychological, moral, internal things. The external threats—up to and including Sauron—are simply narrative facets of those internal dilemmas. It’s sensible, then, that denouement of The Lord of the Rings will be about the internal consequences. For all of our characters, but especially for our hobbits. And most especially, for Frodo.

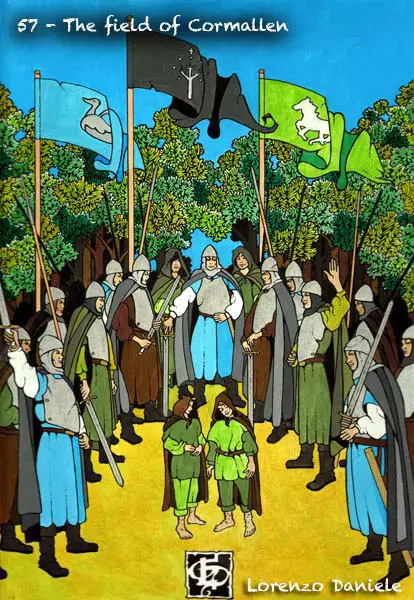

The Field of Cormallen

Tolkien’s whole theory of a proper faerie story hinges on the concept of eucatastrophe, as we’ve touched on many times before. And the Field of Cormallen is the pinnacle of the concept, the whole chapter functioning as a sharp, unexpected turn from the darkness that had come before. After two chapters of torment and devastation everything is suddenly soft, quiet, and feels oversaturated with light and color. It’s the narrative equivalent of a sudden gasp: such an unexpected boon, a joy that pierces like swords.

When Sam awoke, he found that he was lying on some soft bed, but over him gently swayed wide beechen boughs, and through their young leaves sunlight glimmered, green and gold. All the air was full of a sweet mingled sent.

And later:

They stepped out of the beech grove in which they had lain, and passed on to a long green lawn, glowing in sunshine, bordered by stately dark-leaved trees laden with scarlet blossom. Behind them they could hear the sound of falling water, and a stream ran down before them between flowering banks, until it came to a greenwood at the lawn’s foot and passed them on under an archway of trees, through which they saw the shimmer of water far away.

Sam awakes in Ithilien to an impossibly pretty and peaceful scene (just down the road from the waterfall fort where he and Frodo experienced their last bit of real peace). Gandalf is there, laughing, his beard “gleaming like pure snow in the twinkling of the leafy sunlight.” Sam jumps up and laughs, and cries, and when he asks Gandalf “is everything sad going to come untrue?” you almost believe that it will, or could.

This only continues when Sam gets his wish granted almost immediately on the Field of Cormallen and hears himself lodged forever into songs and tales; it continues when he and Frodo run up to Strider who reminds that “it is a long way, is it not, from Bree, where you did not like the look of me?” And maybe most of all when the Fellowship reunites (mostly) and stays up talking together late in the night, entirely unthreatened by Black Riders or orcs or any other immediate or obvious danger.

At last the glad day ended; and when the Sun was gone and the round Moon rode slowly above the mists of the Anduin and flickered through the fluttering leaves, Frodo and Sam sat under the whispering trees amid the fragrance of fair Ithilien; and they talked deep into the night with Merry and Pippin and Gandalf, and after a while Legolas and Gimli joined them.

It does seem like everything sad could come untrue. But that’s not the sort of book we’re dealing with.

Frodo at a Distance

The events of the last two and a half books have obviously made their marks on everyone. Aragorn and Gandalf are more elevated, distant and super-human (since, well, they both technically are). Merry and Pippin utterly baffle Sam with the three inches added to their height and their new status as knights of Rohan and Gondor. Legolas’s sea fixation has only grown:

To the Sea, to the Sea! The white gulls are crying,

The wind is blowing, and the white foam is flying.

West, west away, the round sun is falling.

Grey ship, grey ship, do you hear them calling,

The voices of my people that have gone before me?

I will leave, I will leave the woods that bore me.

For our days are ending and our years failing.

I will pass the wide waters lonely sailing.

Long are the waves of the Last Shore falling,

Sweet are the voices of the Lost Isle calling,

In Eressea, in Elvenhome that no man can discover

Where the leaves fall not: land of my people forever!

Lil’ Melancholy Kid Katie had a lot of feelings about this poem. While I want to make fun of Legolas for sounding like a kid who studied abroad by the ocean for the first time and is applying to MFA programs (or like the inverse of the coastal snob who moves to the Midwest and can’t stop looking down at the Great Lakes), but my heart wouldn’t really be in it. Yearn away, buddy.

But really, I was most fascinated by Frodo in his chapter—or, more specifically, his relative absence. Although Frodo is largely at the center of all the celebrations, he is largely absent from the narrative itself. We skip Frodo’s awakening in order to focus on Sam’s. We get Sam’s reaction to the celebrations on the Field of Cormallen, his reaction to the tales and adventures of Pippin and Merry and the others.

I’d imagine this is largely because, had we gotten Frodo’s reactions to things, this would have been a very different chapter. On the slopes of Mount Doom after the destruction of the Ring, Frodo is hardly cheerful, as he gently puts down Sam’s desire to escape. It may not be Sam’s tendency to give up, he says, “but it’s like things are in the world. Hopes fail. An end comes. We have only a little time to wait, now. We are lost in ruin and downfall, and there is no escape.” For quite a while, at this point, this has been Frodo’s absolute best-case scenario. He would fulfill his Quest, and then he would die. He does not seem to be afraid of this or even particularly upset by it: instead, he faces it with a calm resignation, thinking that this is simply how things have to be.

I’m not sure that I’d go so far as to say that Frodo doesn’t want to be saved. After all, he does seem happy to see Strider again, and to talk with Merry and Pippin and Gandalf under the trees. But it’s also not clear that Sam’s sense of eucatastrophe is shared with Frodo. Even with the Ring destroyed, his emotional status remains unclear and largely blocked off to the reader. Given what he’s just experienced, and what he’s lost, it’s hard not to look at the Field of Cormallen from Frodo’s perspective and feel something sadder, as the poor guy is dressed up in orc garb, saddled with an unwished-for-sword, then forced hear someone sing his trauma at him.

Not much of this is made explicit, of course. But given what’s to come, and how Frodo ended his last chapter, it’s intriguing to me how emotionally inaccessible he is to the reader and how during one of the primary celebrations of the book’s climax he remains inscrutable and tangential. It’s good groundwork for Frodo’s journey after this, and subtly highlights that the emotional and psychological aftermath of Frodo’s experience still needs to be unpacked.

The End of Evil

This interest in the Quest’s ripple effect on individuals is interesting in light of the fact that any large-scale or systemic ripples are almost entirely absent. Sauron himself is literally blown away by the wind:

“The realm of Sauron is ended!” said Gandalf. “The Ring-bearer has fulfilled his Quest.” As the Captains gazed south to the Land of Mordor, it seemed to them that, black against the pall of cloud, there rose a huge shape of shadow, impenetrable, lightning-crowned, filling all the sky. Enormous it reared above the world, and stretched out towards them a vast threatening hand, terrible but impotent: for even as it leaned over them, a great wind took it, and it was all blown away, and passed; and then a hush fell.

And this destructive is definitive and all-encompassing, leaving little-to-no mess to clean up.

As when death smites the swollen brooding thing that inhabits their crawling hill and holds them all in sway, ants will wander witless and purposeless and then feebly die, so the creatures of Sauron, orc or troll or beast spell-enslaved, ran hither and thither mindless; and some slew themselves, or cast themselves in pits, or fled wailing to hide in holes an dark lightless places far from hope.

Though Tolkien is doing this purposefully, I do have a lot of sympathy with those who find this unsatisfying. So much effort is put into the interiority and choice of the Fellowship that it seems… unfair, or narratively unbalanced, to have the forces of Sauron so utterly deprived of a sense of self that when the Ring is destroyed they begin to literally commit mass suicide. I don’t necessarily have a solution for this: frankly, at this point, an in-depth look at what happened to those serving under Sauron would be definitively out of place in terms of theme and tone. But I also think that criticisms on this front are warranted. And that it makes the applicability of Tolkien’s story seem limited, at least in this sphere.

Final Points

- I was intrigued that Gwaihir and his brother were followed by “all their vassals from the northern mountains, speeding on a gathering wind.” I largely ignore the Eagles when talking about Tolkien because I don’t want to talk about whether they should have just flown the Ring to Mount Doom. But I am intrigued by the concept of Eagle vassals. How does air feudalism work.

- Gimli: “I love you, [Pippin], if only because of the pains you have cost me, which I shall never forget.” Harsh but fair.

- It’s very charming that on the day that he was honored as an international hero and the entire global calendar was reoriented around his actions, Sam is bummed he missed out on all those other neat adventures. Orcs, and talking trees, and leagues of grass, and galloping riders, and glittering caves, and white towers and golden halls, and battles, and tall ships sailing, all these passed before Sam’s mind until he felt bewildered. He even missed an Oliphant!

- Prose Prize: There was a lot of gentle, lovely prose this time around. Everything feels especially soft and kind after trucking across Gorgoroth for a few dozen pages. This is my favorite though: And all the host laughed and wept, and in the midst of their merriment and tears the clear voice of the minstrel rose like silver and gold, and all men were hushed. And he sang to them, now in the Elven-tongue, now in the speech of the West, until their hearts, wounded with sweet words, overflowed, and their joy was like swords, and they passed in through out to regions where pain and delight flow together and tears are the very wine of blessedness. Joy like swords is about as Tolkien-y as one can get.

- Contemporary to this Chapter: Everyone’s back together, so we’re retiring this little section this week! So, for the last time: as Frodo and Sam slept for two weeks Celeborn and Galadriel (having already repelled three assaults on Lórien) jumped up to Dol Goldur, destroyed it, and restored Mirkwood. Does this mean the spiders are gone too? In any case, the forest having been cleansed out of its name, Mirkwood is Eryn Lasgalen now, the Wood of Greenleaves. Presumably everyone else sings and cries and takes lots of naps in that dappled Ithilien sunlight.

- We’ll be back on November 15th for “The Steward and the King.” Please brush the dust off of your favorite Eowyn/Faramir fanfiction from middle school (Middle-school) and review it, it will be on the test.