“You are a set of deceitful scoundrels!” he said, turning to the others. “But bless you.”

“A Conspiracy Unmasked” covers much of the same ground as earlier chapters: there is the regret of leaving home we found in “Three is Company,” there is the reliance upon friendship and the care of others that we saw in “A Short Cut to Mushrooms.” But this time we also get something new. “A Conspiracy Unmasked” is a turning point in The Lord of the Rings, in the movement of both its plot and its themes. We really get going for the first time: with all the white lies and cover ups about staying in Crickhollow swept away, our hobbits make their plans to set off beyond the borders of the Shire, beyond the High Hedge, and into the Old Forest. Things are getting Serious™.

This starts from the very beginning of the chapter, when Frodo, Merry, Sam, and Pippin cross the Brandywine and approach the monumental (by hobbit standards) Brandy Hall, fronted by three doors and a hundred windows glowing softly yellow and red. Buckland is an extension of The Shire – “a sort of colony,” Tolkien calls it – but it’s unquestionably different, filled with hobbits who like boats and who live with their backs up against the Old Forest and the outside world. And at the chapter’s close we get one of the most unsettling scenes so far: Frodo’s dream of a tower rising high over a dark heath. But at the same time, we also have one of the most emotionally intimate and touching scenes, as Merry & Co. reveal their “conspiracy” to prevent Frodo from slipping out of the Shire alone.

“The Inquisitiveness of Friends”

The scene in Crickhollow calls back to the intimacy and warmth that was on display at Farmer Maggot’s dinner at the end of the last chapter: hot baths, warm food, good friends, the calm before the storm. The themes here are similar, but heightened: having allowed himself the help of Sam in “A Short Cut to Mushrooms,” Frodo is still afraid of spreading the potential damage any further. He talks around the situation, refusing to name the problem but also telling his friends that he is “not safe here or anywhere else.” But Frodo, we find out (and probably could have guessed), is not the world’s best secret keeper: Merry, Pippin, and Fatty Bolger already know the majority of his situation, and have taken extensive steps to help him – and more importantly, to make sure that he doesn’t try to go alone.

It’s a really kind, lovely scene, rooted in how well these characters understand and care about each other. It also illustrates how well they balance each other out, each personality shining through in how they react to the situation. Frodo is the one who inspires loyalty, mostly through his sensitivity: he wants to protect his friends from impending danger, but is also able to recognize how little of that power remains in his hands. It’s mentioned near the end of the chapter that even Fatty Bolger, who plans to stay behind in Crickhollow, may well be more in danger than the rest of them, despite their path leading them into the Old Forest. And once again, Frodo shows that – despite some half-hearted attempts at showing dismay at their conspiracy – he is willing to accept help that is genuinely offered. And finally, we see how far out of his element Frodo really is.

The last few chapters have been shown predominantly through the perspectives of Frodo, and all things suggest that he’s doing a fairly good job keeping things under wraps. But then we get this reveal from Pippin: “You have obviously been planning to go and saying farewell to all your haunts all this year since April,” he says to Frodo. “We have constantly heard you muttering ‘Shall I ever look down into that valley again, I wonder,’ and things like that.” This made me laugh a lot the first time I read it, but if you spend any time at all thinking about it, it’s sad on so many levels. Not only does it highlight how sensitive Frodo is, but also how unprepared he is for this kind of mission. Frodo is a wonderful character so far, layered and multidimensional. He strikes one, at this point, as far too open and vulnerable to take on this kind of mission, and every chapter further in I feel a growing need to protect poor Frodo and make sure that he’ll be okay.

Luckily, he’s got quite a band coming along with him. Pippin remains largely comic relief – splashing bath water around and praising Sam’s worth as long as he doesn’t trip over his feet into dragons’ mouths – but in a delightfully self-aware way. He never seems particularly dim, as his movie counterpart usually does. Sam continues to be the best, revealing his secret role as Merry & Pippin’s super spy! Sam’s embarrassment about this is perfect, as is the fact that – once caught by and recruited by Gandalf – he viewed himself as “on parole” and shut down his spying routine immediately.

But I think the real star of this chapter is Merry, who comes into his own for the first time. He’s revealed as the mastermind behind the plan, having discovered at least a partial truth about Bilbo’s Ring several years before. He’s a natural, inquisitive leader right from the start, curious and driven by his care for Frodo – “We have been terrified that you might give us the slip,” he says, explaining why he felt the need to spy. He also shows a great deal of emotional insight when Frodo complains that it seems he can’t trust anyone at all:

It all depends on what you want,” said Merry. “You can trust in us to stick to you through thick and thin – to the bitter end. And you can trust us to keep any secret of yours – closer than you keep it yourself. But you cannot trust us to let you face trouble alone, and go off without a word. We are your friends, Frodo. Anyway: there it is… We are horribly afraid – but we are coming with you; or following you like hounds.

Teenager Katie had a big crush on Meriadoc Brandybuck, and Present Day Katie surprisingly approves. Merry is great so far. Clever, curious, kind, and a good leader.

Frodo’s Dream

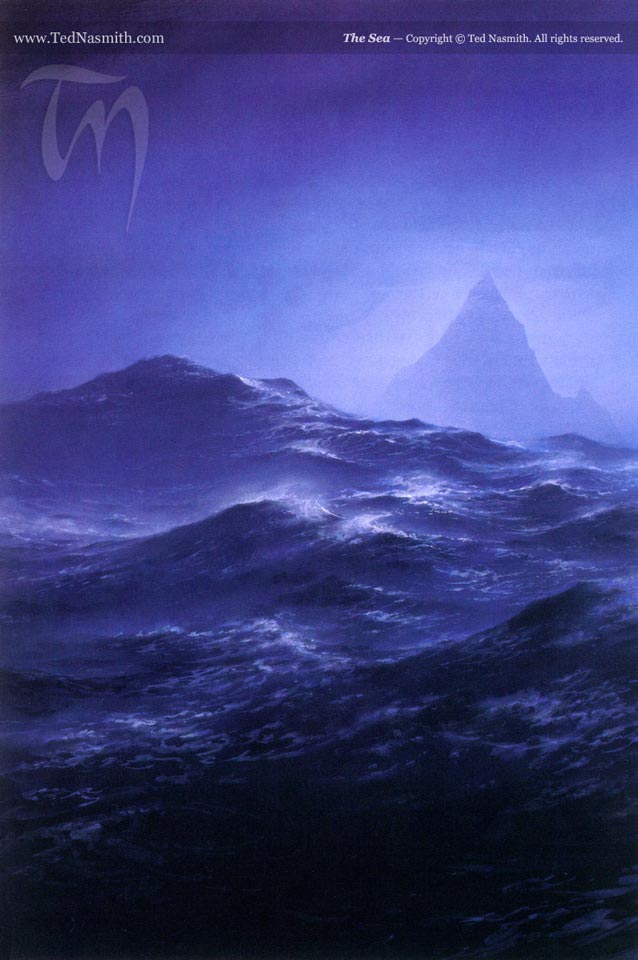

Eventually he fell into a vague dream, in which he seemed to be looking out of a high window over a dark sea of tangled trees… Then he heard a noise in the distance. At first he thought it was a great wind coming over the leaves of the forest. Then he knew that it was not leaves, but the sound of the Sea far off; a sound he had never heard in waking life, though it had often troubled his dreams. Suddenly he found he was out in the open. There were no trees after all. He was on a dark heath, and there was a strange salt smell in the air. Looking up he saw before him a tall white tower, standing alone on a high ridge. A great desire came over him to climb the tower and see the Sea. He started to struggle up the ridge towards the tower: but suddenly a light came in the sky, and there was a noise of thunder.

When I first read The Lord of the Rings, I was obsessed with this passage. I read it over and over again, and (along with a select group of other passages we’ll get to later), I memorized it and would repeat it to myself in my head when I was scared or sad. I’m not sure that I could have told you what it meant: just that I knew that the Sea was important for some reason, and that I related to the idea of feeling any overwhelming need to see something just over the line of the horizon. The whole thing reminds me of walking outside in the summer, and feeling that heavy sense of potential that comes right before a thunderstorm.

I’m still not sure what it means. Part of me wants to interpret it, and pick apart its meaning, but the other part of me wants to keep in mind Tolkien’s distaste for allegory, and to let it sit as the atmospheric cap to the chapter. In either case, the presence of the Sea works well here: it pairs nicely with the crossing of the Brandywine at the start of the chapter, calling to mind all the mythological overtones associated with crossing bodies of water. Sam picks up on it: “he had a strange feeling as the slow gurgling stream slipped by: his old life lay behind in the mists, dark adventure lay in front.”

Crossing water here sets the hobbits off on a new stage of their adventure, and the reference to the Sea at the end may simply serve to remind the reader that Frodo & Co. are in the midst of being drawn into a much wider, bigger story. It seems like the tower in the dream is most likely Emyn Beraid, the Tower Hills to the West of the Shire. It has a long history of its own, founded by Gil-Galad and the home of a Palantir that sees into the West and the home of the Valar.

It’s also, as we’ll see in The Return of the King, the eventual home of the Red Book of Westmarch. It’s interesting – if this is the tower of Frodo’s dream – that the dream centers around a place that was important to ages of the past but also to the eventual endpoint of Frodo’s journey, a physical place where the past and the present (and the future) coexist. There’s a part of me that likes this interpretation, since it fits nicely with Tolkien’s persistent sense of history. But it’s also possible, of course, to simply see this as an atmospheric coda to the chapter, a foreboding reminder that even with the support of friends there is plenty of uncertainty to come.

There’s one more thing about Frodo’s dream that I’d like to bring up before we finish off for the week: these ideas come largely from Simon Cook’s recent essay “On the Shore of the Shoreless Sea.” Cook points out that the image of the tower from which one can see the Sea pairs almost perfectly to a metaphor used in Tolkien’s famous essay on Beowulf, “The Monsters and the Critics.” Tolkien pointed out that – in their eagerness to pick apart the antecedents and influences of the Beowulf poet – literary critics had largely dismantled the poem, forgetting that “from the top of that tower the man had been able to look out upon the sea.”

Another moment in “The Monsters and the Critics” is also reminiscent of Frodo’s dream: Tolkien speaks of “the eormengrund, the great earth, ringed with garsceg, the shoreless sea, beneath the sky’s inaccessible roof; wherein, as in a little circle of light about their halls, men with courage as their stay went forward to that battle with the hostile world and the offspring of the dark which ends for all, even the kings and champions, in defeat.” Northern poetry like Beowulf, for Tolkien, was heavily characterized by this sense of bravery in the face of inevitable defeat. Heaven was distant, inaccessible, the sea was deep and dark, hope came from singular moments close to home, surrounded by impending darkness.

Frodo’s dream is very pertinent in this sense. In the midst of warmth and friendship, right before he’s forced to start his journey, he’s drawn to look out over dark trees, thunderous skies, and the endless expanse of the Sea. It’s an ominous moment, filled with foreboding, but it’s also very interesting in how it will compare to later depictions and visions of the Sea in The Fellowship of the Ring and beyond. Tolkien’s other academic works (as Cook points out) also explore the ancient literary trope of a savior king coming from across the sea, introducing the possibility that the Sea is not just ominous, but also full of promise. It’ll be interesting to see how this develops over the course of The Lord of the Rings.

It’s possible I’m reading too much into this, of course, but I always like to see how Tolkien’s medievalist background worked its way into his creations. And it’s a good reminder that Tolkien was usually working on so many levels, where even the smallest reference can have long-reaching associations.

Final Comments

- “Oh! That was poetry!” said Pippin, after singing a song inspired by Bilbo’s dwarven friends of The Hobbit. “Do you really mean to start before the break of day?”

- How does everyone feel about Fatty Bolger? I was a little bit judgey about his decision not to go with Frodo, I have to admit. But I also worry that, if it really came down to it, I’d be a Fatty Bolger too.

- My Dad mentioned to me that Frodo’s quote “If the danger were not so dark, I would dance for joy” captures the whole chapter pretty well. I think he’s right.

- Prose Prize: The above quote from Frodo’s dream. Of course.

- Art this week is from Ted Nasmith, entitled The End of an Age and The Sea. I had trouble getting permission for many of the images that I would have liked to use this week, so I’ll have to send you off site for them: Diego Gisbert Llorens has a nice depiction of the hobbits at Buckleberry Ferry and Francesco Amadio has one of my favorite images of the Tower Hills west of the Shire.

Next Time: “The Old Forest,” a chapter about which I remember almost nothing!