It seems the Senegalese director Ousmane Sembéne is destined to be “rediscovered” every few years. Known as the godfather of African cinema, he is the most well-known director from the continent and one of the lesser-known directors among casual cinephiles. This is primarily because the countries of Africa have not had the luxury of becoming synonymous with a specific genre that has taken off across the globe, and the political realities forbidding them from even making films.

Sembéne took to filmmaking late in life. A novelist, he prefers books to film and, unlike many directors, is not obsessed with the craft. He is, however, obsessed with the political ramifications of art, being a native of an occupied country that was granted its independence during his lifetime. For Sembéne, “Cinema is like an ongoing political rally with the audience.”

He took up filmmaking because he saw that film, for all its faults, could reach a larger audience. “I prefer literature. But in our time literature is a luxury.” Since many in African countries must know an array of different languages, from the official language of the occupier to their native tongue, which may or may not be banned, to the language of the next colonial power, they are left without a language of their own and often without a support system to learn it. Cinema, however, reaches across these limitations, and Sembéne saw that and began to use it to wield his attacks on the vultures he witnessed feasting on his beloved country of Senegal and the other African countries.

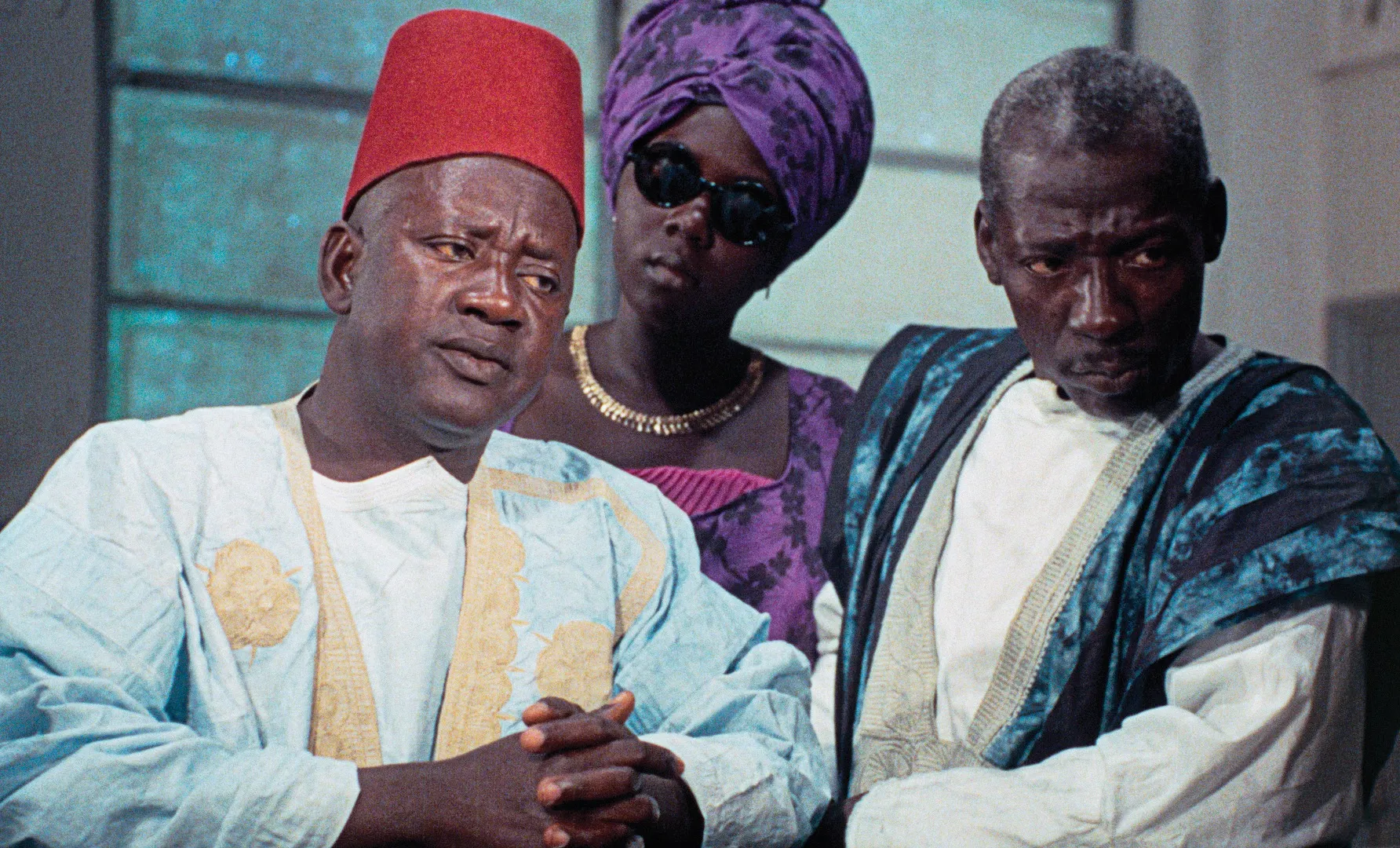

His fourth film, 1968’s Mandabi (The Money Order), and his first in color is, like Sembéne himself, widely known but little seen. Sembéne believes other countries refused to show the film because they thought it could only happen in Africa. This is an unfounded belief, as anyone who watches Mandabi will quickly see a universal act of trying to navigate a complex, corrupt, and often dehumanizing bureaucracy. A straightforward fable, Mandabi is about an unemployed Muslim man, Ibrahima (Makhourédia Guèye), who receives a money order for twenty-five thousand francs and how his attempts to cash it lead him to further ruin.

What should be a simple task, cashing a money order, becomes a complicated and morale-destroying series of events. It’s too big for Ibrahima’s local post office to cash, he needs someone to read the letter to him because he doesn’t speak French, the city hall won’t cash his money order without an identity card or some form of picture identification, and you can see where this is going. But in Sembéne’s deft hands, Mandabi becomes a tragic comedy.

Mandabi is based on Sembéne’s book and continues with the themes of his first short, Borom Sarret (The Wagoneer). Though only twenty minutes, the short shows a remarkably concise and complex critique of the newly independent Senegalese and the effects of capitalism and colonial powers. It’s so adept visually and thematically that it’s hard to believe it’s a first film. Likewise, Mandabi is Sembéne’s first film in color, and again, it feels like an old master instead of a new student.

Sembéne resisted shooting in color for fear of exoticizing the skin tone of his stars. But realizing that color could be used as a dialectical tool, he embraced it. Ibrahima, his wives, and his neighbors in the Dakar shanty town are dressed in vibrant, sumptuous colors. Meanwhile, the bourgeoisie, members of the uncaring bureaucracy, and people who live in the newer part of Dakar are dressed in drab browns and ordinary suits. Because Sembéne understands the poorer one is, the more tries to appear not as poor.

He also understands that Guèye’s Ibrahima can not be a saint or a martyr. In the beginning, we see Ibrahima gorging himself on his meal. He eats it so fast he gets indigestion. Sembéne and Paul Soulignac’s camera shoot the scene almost sensually. Close-ups of his hands as he licks them clean or his face as he gobbles the food show us Ibrahima’s pleasure in eating. At the same time, Sembéne and Soulignac show that Ibrahima is an arrogant fool. We are not spared his burping and attempts to pass gas or call out to his wives, played by Ynousse N’Diaye and Isseu Niang, to massage his legs.

A remarkable aspect of Mandabi is how most of it occurs outside. Scenes briefly take place indoors, but most of the film occurs outdoors. The lack of soundstages adds that pint of cinema verite, a trademark of Sembéne’s. Along with the use of natural settings, Sembéne and Soulignac will, in addition to the colors of the costumes, use lighting as an indication of the morality of the scene. For example, the scene with M’barka the shopkeeper takes place in the shadows, indicating the moral dubiousness of the conversation. Artificiality and the lack of it play a key role in Sembéne’s film both as an aesthetic and as a tool for instructing his audience.

Sembéne took a cue from the Italian Neo-Realists and populated his movies with a mixture of non-actors and actors. Guèye is a trained actor, making his early scenes a mix of observation and slapstick. His Ibrahima is natural, and it’s easy to think he is one of the non-actors. He never plays Ibrahima for laughs; instead, he plays him as what he is: a man prone to foolish mistakes without playing him as a fool.

Ibrahima’s child is left alone outside, crying for his mother while she must attend to his father’s needs. Throughout Mandabi, we never hear Ibrahima ask or talk about his seven children. Sembéne deliberately makes Ibrahima a flawed man because whether or not he’s a good husband, father, or man doesn’t excuse what happens to him. At the same time, Sembéne is rarely one-sided with his critique, recognizing that while the power and majority of the blame lies with the system, the people are not blameless.

One of the ways he shows this in Mandabi is that after Ibrahima receives the money order, he goes to the local shop. M’barka (Mustapha Ture), the shopkeeper, has heard of Ibrahima’s good fortune and tells him of some expensive rice he has in the back. A child comes in and asks for some rice, and M’baraka tells him he has none while Ibrahima stands by, flattered by the offer.

However, Sembéne is rarely satisfied with caricatures. Later, we see Ibrahima give money to a woman who needs bus fare. Ibrahima is neither good nor bad; he’s simply a man trying to get by in a world designed by people with no thought or love for those who live there.

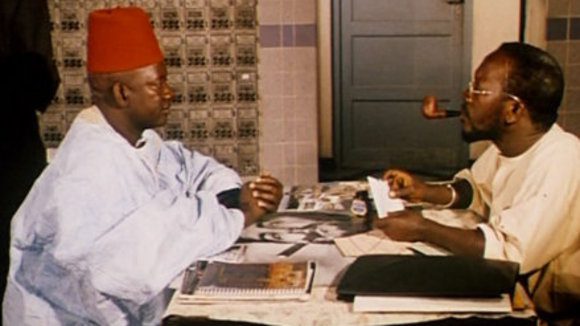

Every opportunity for Ibrahima only turns into another stumbling block. Ibrahima takes the letter to a public reader, played by Sembéne himself, and learns that the twenty-five thousand francs is from his nephew, who has gone to France to try and make his fortune. Twenty thousand is meant for Ibrahima to put aside for the nephew, three thousand for the boy’s mother, and the other two thousand for Ibrahima. It’s not quite the windfall Ibrahima hoped for, but three thousand francs is better than nothing. Though he’s rapidly spending the money he doesn’t have as debt and obligations pile up around him.

It’s not the bureaucracy Ibrahima has to worry about, however. The hucksters, the religious leaders in his neighborhood, and predatory realtors are all looking to get a share of Ibrahima’s windfall. The local Imam asks for a donation from Ibrahima, claiming he is in dire straits. Yet, we see him grousing with another person about Ibrahima, a neighbor who only succeeds in getting a few pounds of rice from Ibrahima. The two eat together and plot how to try better and get Ibrahim’s money.

For Sembéne, religion is not the enemy, but it is a cultural enemy. A church that does little more than take tithing not from those who can’t afford it and do not give back to the community is a parasite that does not deserve to live. It’s the way Ibrahima uncritically engages with his religion, his willingness to take gifts at the cost of a child starving without riesling that if he would do so, then what is to keep someone from doing the same to him?

The shopkeeper also runs a pawn shop and charges outrageous interest rates with little time to pay it back. Moments like these made me laugh at how people claimed Mandabi couldn’t happen in their country. I have rarely seen a nakedly pure example of Payday Loans then I have in Mandabi. The shopkeeper and his co-workers are moral when it comes to their payment but immoral in how they go about setting the impossible terms.

Even when Ibrahima tries to do the right thing, the game is rigged. He is poor and unemployed, so he attempts to get a picture taken for his ID. He goes to the cheapest photographer, who promises him that for three hundred Francs, he’ll have it the next day. It is a scam that becomes apparent the moment Ibrahima leaves. When Ibrahima strikes back, the photographer plays innocent like the shopkeeper. But he shrugs when a neighbor warns him that people will get wise to his scam one day. “In this country, only the crooks live well.”

Sembéne’s criticism of colonialism is razor-sharp. Mandabi is the first film ever shot in the Wolof language, the native language of the Sengalise and other countries. The very language the characters speak showcases the linguistic hurdles of knowing the official and unofficial languages, especially when the official language changes. When asked for his signature, Ibrahima asks if they want his French name or Arabic.

Mandabi showcases Sembéne’s rich humanistic observations and scathing intellect as he parses complex problems without giving simple answers. As Mandabi unfolds, we can’t help but laugh but also feel a growing anxiety as the only luck Ibrahima has is bad luck. It is a testament that by the end, the final screw in Sembéne’s script made my stomach drop. The ending has a ray of hope, with Sembéne speaking to us, the audience, through the character of the postman. Yet, my heart went out to Ibrahima as it all became so horribly overwhelming.

Sembéne wisely observed, ”We all want revolution and change. But we want someone else to do it for us so we can enjoy it.” His films radiate pragmatic humanism with an eye for detail and an understanding that problems are often much more complex than our anger toward them. But it’s hardly any excuse not to be angry or to try not to solve them.

Images courtesy of The Criterion Collection

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!