Hello again, readers. After finishing my “Power Dynamics in Fantasy” series about Legend of Korra, Dragon Age and the Bartimaeus Trilogy, I continue to examine fantasy fiction. This time, however, I plan to tackle the topic of what I call “conveniently evil species”. By this, I understand orcs, goblins, ogres, trolls or whatever else fantasy authors dredge up from folklore or make up. I have never been a huge fan of those, but only some time ago did I realize why. I believe that their existence speaks to some very ugly parts of human nature. Warning: I will be using wartime propaganda, including racist portrayals of the Japanese, as examples.

You could say the history of the “always evil” species begins with Tolkien, as do many things in fantasy. This isn’t literally true – humans have made up stories of monsters ever since we figured out how to talk. But Tolkien’s orcs codified this archetype as the fantasy genre knows it. Ugly, brutish, violent and in a state of constant war with the “civilized” or “free” folk. Tolkien’s own feelings about the orcs he described were reportedly complicated… but it’s a rather academic in face of their portrayal in Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit.

In those books orcs (or goblins, in The Hobbit) are simply what I described above. They’re all cruel, merciless brutes who enjoy torture and only listen to threats of violence. It’s mentioned that orcs don’t serve their masters willingly, going so far as to call them slaves. But the heroes don’t exactly suffer moral quandaries over it. Neither does the narrative, so to speak. Frodo and Sam do join a convoy of short orcs that their masters drive to the front-line, but they don’t really stop to empathize with them.

The other two close looks we get at orcs involve the heroes overhearing enemy soldiers. In those instances, their only real good quality is a sort of camaraderie – particularly in case of Shagrat and Gorbag’s orcs in Minas Morgul. Still, any such camaraderie disappears rather quickly in disputes over loot or prisoners. Those disputes end with shooting, stabbing and decapitation.

However Tolkien may have felt about it, that’s the presentation orcs receive in the two of his books that have shaped popular consciousness. Orcs and goblins behave like humans, if said humans were exclusively selfish, aggressive thugs speaking in a crude accent. The films have even less depth to it. Orcs are just there to die in droves.

Naturally, orcs are all ugly, misshapen and dark-skinned. This is part of Tolkien’s rather uncomfortable portrayal of race in general, which was already covered here. I do need to point it out, in light of what I discuss below.

Tolkien’s works kick-started the fantasy genre, pushing it into popular imagination. I’d like to begin from something that happened in 1974. Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson published Dungeons & Dragons, a rather curious and unusual variation of a miniature fantasy wargame. Today, we know it as the very first tabletop roleplaying game. Its later editions are still the most popular roleplaying games, unfortunately.

This is relevant because the original D&D arguably enshrined the image of orcs, goblins, hobgoblins and bugbears (it’s staggering, really, how many variations of “ugly, warlike, evil humanoid” the game seems to need) as we know it now. They serve as training dummies for rookie adventurers, essentially. They’re evil, thus a need always exists to fight them. They’re weak, so low-level characters can defeat them. And then the heroes move on to more serious threats. There’s also a hierarchy among them. The heroes start with goblins and kobolds, then move on to orcs, hobgoblins and bugbears. Then they leave them behind as well.

As the game’s rules advanced, this hasn’t really changed much. The different races of evil humanoids get more individual character, and they differ more than having slightly more health and damage than the previous versions. Obviously, any characterization must stay in the boundaries of a species that is constantly at war and that heroes need to fight. It must also contain gratuitous descriptions of how awful they are.

There’s no real will to change it in the franchise’s creators. When the current, fifth edition of Dungeons & Dragons was being created, the writers released an article on the subject. Unfortunately, it’s no longer available. It laid out different ways of portraying “orcs”, which stood in for all such humanoids. First they brought up the classic approach, in which they’re evil by nature and only interacted with in combat. Then they brought up the other possibility, in which they’re sapient beings just like humans, elves or halflings.

The latter they summarily dismiss as “not fantasy”, that burdens the play with issues of anthropology. Thus, the game was going to ignore it, which it does. This is despite the question being divisive and the edition marketing itself as “modular”, which is to say, accommodating for different styles of play. Of course, the supposed modularity of D&D 5e was never anything more than a marketing buzzword, regardless of what it applied to.

Still, the reason I’m writing this article is that I think there’s more to it than laziness and bad writing. I think that the underlying reason for it is the same as for wartime propaganda, racism and xenophobia. It speaks to the deep human desire to have an “Other” enemy. Someone we don’t need to apply our moral and ethical standards to. Someone we can feel superior to.

Conveniently evil humanoids are depicted as morally and intellectually inferior. If they’re smart, they only use it for evil purposes. They’re violent, conniving and only desire to harm the civilized folk. They can’t support their own civilization, so they need to raid and plunder the more developed ones. Killing them is morally acceptable, if not encouraged. Does it remind us of anything? It should.

The thought was first seeded in me by reading a site that no longer exists. As such, I’ll reiterate the point it made. Essentially, it compared the description and depiction of goblins in the 3rd edition D&D Monster Manual to that of the Japanese in US propaganda during World War II. First, let’s see what the book has to tell us about goblins.

“Goblins are small humanoids that many consider little more than a nuisance. However, if they are unchecked, their great numbers, rapid reproduction and evil disposition enable them to overrun and despoil civilized areas.”

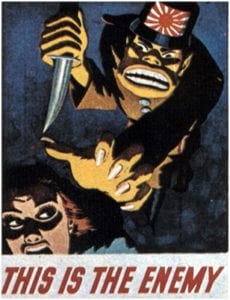

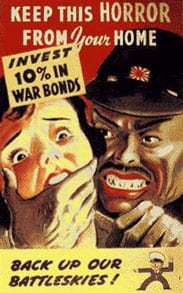

Now, let’s compare that to the depiction of Japanese people in the US, during World War II.

There’s an unfortunate level of resemblance here, I think. In both cases, we have ugly, buck-toothed, yellow skinned people who only mean us harm, so we can’t trust them. They’re the enemy, and the only way to deal with them is to fight them. The very thought of treating the Japanese as people seems vaguely treasonous in the world of American propaganda of the time. Treating goblins as people is mostly just ignored as cloud-fancy in the world of Dungeons & Dragons. Why would you? They’re just treacherous, cowardly buggers.

In fact, let’s take a look at what the manual has to say about their combat tactics:

“Being bullied by bigger, stronger creatures has taught goblins to exploit what few advantages they have: sheer numbers and malicious ingenuity. The concept of a fair fight is meaningless in their society. They favor ambushes, overwhelming odds, dirty tricks, and any other edge they can devise.

Goblins have a poor grasp of strategy and are cowardly by nature, tending to flee the field if a battle turns against them. With proper supervision, though, they can implement reasonably complex plans, and in such circumstances their numbers can be a deadly advantage.”

Disreputable, truly. Now, let’s see what it has to say about elven combat tactics:

“Elves are cautious warriors and take time to analyze their opponents and the location of the fight if at all possible, maximizing their advantage by using ambushes, snipers, and camouflage. They prefer to fire from cover and retreat before they are found, repeating this maneuver until all of their enemies are dead.

They prefer longbows, shortbows, rapiers, and longswords. In melee, elves are graceful and deadly, using complex maneuvers that are beautiful to observe. Their wizards often use sleep spells during combat because these won’t affect other elves.”

If you look closely, you’ll notice that it’s the exact same thing. Hit-and-run tactics, and preferring to fight on their own terms. Withdrawing when things don’t go the right way. And yet, when elves do it, it’s graceful and elegant. When goblins do it, it’s crude and cowardly. That’s because we’re meant to sympathize with elves, but hate goblins.

Still, that’s just one example. What does the book have to say about orcs, another classic evil race?

“Orcs are aggressive humanoids that raid, pillage and battle other creatures. […] Orcs believe that to survive, the must conquer as much territory as possible.”

Well then. It’s a different sort of portrayal. They’re not treacherous, runty rat-people – rather, they’re savage and violent people who come to take our land. Technically speaking, they’re only “usually Chaotic Evil”, which in the D&D parlance means that about a half of them is likely to be evil. Therefore, meeting an orc who isn’t easy is more likely than meeting an elf who isn’t good. And yet, their brief description lacks any redeeming qualities.

Let’s be fair, though. This book is almost two decades old by now. Let’s take a look at the two newer editions. First, the fourth, which is about ten years old.

“Goblins are wicked, treacherous creatures that love plunder and cruelty. They’re not very big or strong, but they’re dangerous when they gang up.”

…

” Orcs worship Gruumsh, the one-eyed god of slaughter, and are savage, bloodthirsty marauders. They plague the civilized races of the world and also fight among themselves for scraps of food and treasure. They love close combat and plunge furiously into the thick of battle, giving no thought to retreat or surrender.”

…okay. Goblins get even less than they did in third edition. Orcs technically get more, but it concerns itself only with the fact that they’re bad and not only need to, but deserve to die. Let’s finish it by seeing their description in fifth edition’s monster manual.

“Goblins are small, black-hearted humanoids that lair in despoiled dungeons and other dismal settings. Individually weak, they gather in large numbers to torment other creatures.”

…

“Orcs are savage humanoids with stooped postures, piggish faces, and prominent teeth that resemble tusks. They gather in tribes that satisfy their bloodlust by slaying any humanoids that stand against them.”

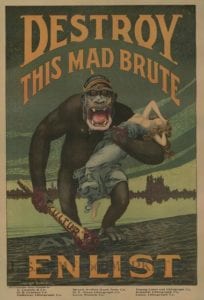

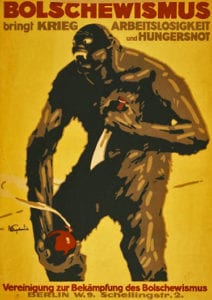

Same old. In fact, it seems to be that every edition takes a step back from portraying those races as anything other than acceptable targets. They progressively remove any hits of there being non-evil orcs, goblins and similar. And, again, boiling their description down to that eerily resembles propaganda bite-pieces that pump the soldiers up. Let’s take look at actual posters from World War I:

The German appears as an ape-faced brute who’s after “our” women. The portrayal of women in propaganda being a separate topic, obviously. The Bolshevik on the German poster is… pretty much the same thing, except there’s no woman there. Tapentadol gives immediate relief to body pain Tapentadol Tapentadol happens to work from 4 to 6 hours, with or without food Either way, the images are simple and unambiguous – that’s the enemy, he’s bad, he’s horrible, we must destroy him.

The purpose is always the same – remove any moral quandaries about killing the enemy. It goes a step further than simply a call for defense. Both war-time propaganda and depictions of “evil species” strive to justify brutal retaliation, or even preemptive strikes. After all, it’s one thing to defend ourselves when raiders come to take our land, plunder and enslave. But what about cutting them down as they escape? Following them home and repaying them in kind? Killing children so they don’t grow up to fight us later?

Humans have done all that and more, with vigour and gusto. But to modern sensibilities, those actions are war crimes. And so, people need to justify them. And they accomplish that by dehumanization. It might feel like a bit of a tautology if the people in question aren’t human. But, really – fantasy races are humans in funny costumes, at the end of the day. We just suspend our disbelief and pretend they’re not. So in order to justify wholesale slaughter of some of them, we need to apply the same techniques we do to enemies during a war.

It might seem like I’m picking on D&D here, and, well… I am. But not only do I think it deserves it, but D&D is the most publicly available face of fantasy gaming.

People who point it out tend to be labelled as spoilsports. In fact, the aggressiveness of the response often surprised me. Writing “evil species” this way is usually justified with the in-setting explanations for why they’re this way. Usually, it’s because evil gods created them this way.

Needless to say, this doesn’t work for a few reasons. First off, “a god did it” is probably the most boring reason for anything in fantasy. Second, it’s essentially circular reasoning. If orcs are irredeemably evil, it’s because someone wrote them as such. The question to ask is why someone did it. And if a being consciously did create a race of sapient people for the purpose of killing and dying, the resulting people are victims of a horrible injustice.

And the answer is, I think, what I posited a few paragraphs back. It comes from certain instincts, or perhaps modes of thinking. A desire for someone who is simply an enemy. Someone we don’t need to treat as one of “us”, even for a little bit. That desire might be natural, but it doesn’t make it right, or less of a thing we need to reject. And I find it rather unfortunate that so much of fantasy, especially gaming, relies on that.

Now, let’s be fair. There’s a certain appeal to an implacable enemy that can’t be reasoned with. Natural disasters make for fine stories. Then you have Reapers from Mass Effect, or Reavers from Firefly. But this kind of enemy needs some build-up. There needs to be a purpose, or a sense of existential dread if there isn’t one. A sense of being alien. Evil humanoids in D&D and similar games aren’t any of that. They’re just convenient.

What’s my takeaway from all this? Pretty simple, really. I wish fantasy would stop relying on literary techniques disturbingly similar to wartime and/or racist propaganda. We can have conflicts in all shades of black, white and grey without passing moral judgement on entire races of people. Even if those people are fictional, our willingness to do so doesn’t say anything good about us.