So we’ve talked a fair bit about 2018’s Detroit: Become Human. We’ve talked about the overall narrative and itis botched parental storyline. Now, we get to talk about a subject that’s very fun: the android known as Connor.

Out of all the protagonists, Connor has one of the most diverse arcs witnessed in game. He straddles the point between hero and villain, and no matter his path, remains a victim throughout, though unknowingly. He’s eager, determined, and curious, brimming with emotions that he doesn’t understand and continues to deny. And the tragedy of his story, his inability to connect with others save a few, makes his tale, despite being one of three, the primary one throughout and one, despite it’s more down-to-earth nature, that is nonetheless an important commentary on the world we live in.

Beware that the following content contains heavy spoilers, so if you haven’t finished your gameplay, go and do so! And if what I’ve said so far sounds like your kind of entertainment, you can purchase the game through PlayStation, or if you’re a PC gamer, it is available through Steam and Epic Games.

The Divide

Connor, first and foremost, is established as a “traitor” in his narrative. The very first mission of the game has Connor resolving a hostage crisis with an interesting twist: the hostage is a child and the hostage taker is her soon to be decommissioned family android. It’s a delicate situation with various outcomes and paths to take towards resolution. The best of these conclusions involves Connor saving the life of a bleeding out police officer and rescuing the child with no damage taken to himself. But there are two moments in this sequence that draw attention to both Connor’s nature and how his narrative plays out in the game.

The first, in which Connor creates a tourniquet for the aforementioned police officer, has a moment in which the hostage taker – Daniel – shoots at him and demands he step away from the dying man. While Connor can choose to walk away, staying triggers this comment:

“You can’t kill me – I’m not alive.”

This is an interesting quote. So much of this mission relies on you playing amateur hostage negotiator, which includes emphasizing with the recently deviated and distressed Daniel. In fact, when he first begins to approach the skittish Daniel on a high rise rooftop, Connor mentions the fact that he is like Daniel – an android – in an attempt to soothe him.

Daniel in this moment has discovered his sense of self and declared himself a living being and one worthy of being treated as such. Connor’s vehement denial of himself (and by extension Daniel) being “alive” immediately sets him apart from Daniel in this situation despite his earlier words. The two are the same, and yet Connor is startlingly different.

The second moment occurs at the very end, if the player has managed to achieve the most “successful” route. After promising Daniel that he will be able to walk away, Connor can eventually persuade him to release his hostage. In the next moment, through no order of Connor’s, Daniel is struck a multitude of times by human snipers on adjacent buildings.

It’s a haunting scene: a slow-motion showing as parts of Daniel are blown off in sprays of metal, plastic, and blue lifeblood. A shot as the dying android sinks to his knees. His last words uttered through a ruined jaw, stuttering and echoing as his systems shut down, eyes locked on the person he might have called kin, damming him with his final (metaphorical) breath:

“You lied to me Connor.”

This moment will set the stage for how Connor is seen by his community (or what should arguably be his community) for the rest of the game.

A liar. A traitor.

This position is unenviable…and inevitable. Like Kara and Marcus, Connor’s path can lead him to being either hero or villain. Unlike the other two however, his journey has both leeway and tighter restrictions.

Tallying Humanity

Detroit employs a quiet point system that determines how each character’s interactions with close NPCs (Non-Playable Characters) play out, which in turn determines how the stories of all involved end. For Markus, the player must weigh actions that have negative or positive effects on “public approval” that will help or harm his android rights cause. For Kara, you weigh actions that will more directly impact your relationship with psuedo-daughter Alice, and any allies you come across. Connor must weigh his relationship between his two handlers, Hank and Amanda, and on a more personal level, his “software instability.”

Nearly every action Connor takes affects his “software instability” level, either immediately, or in the long run. The greater this level, the more “human” options and choices are presented to him. Effectively, while the game touts three protagonists, the player will begin to realize that the true story – “Becoming Human” – revolves around Connor.

What makes Connor unique compared to his fellow protagonists is that he has the ability to die numerous times and return healthy and hale – to a point. His resurrections come at a cost, though; like a futuristic Lord Beric, each time Connor is brought back, he loses a piece of himself – namely, his build-up of “software instability.” Effectively, while all the other androids are granted or gain freedom/humanity all at once, Connor is once again set apart by his journey to sentience being reduced to a slog, one that can be reset at any moment.

But as we see in the aforementioned incident with Daniel, what it means to be considered human is…tricky. To be deviant in the context of Detroit is to be on the same level as humanity. Those who are not deviant are considered to be still in bondage; they only have to be shown what they can be, what the world is beyond their programming. What they do prior to that moment of freedom is beyond their control – it’s simply not their fault.

The same truth does not apply to Connor.

To other androids, Connor’s very position as a representative of an oppressive regime (Cyberlife, the company that creates him and all other androids and the police department, who is trying to get a handle on what they see as a deviant crisis) makes him untrustworthy and even a bit unworthy of the same respect all other un-awoken machine would be granted by their free fellows.

Take one of Connor’s missions for example, in which he is tasked to investigate the aftermath of deviant androids break-in to a broadcasting studio. After looking around and making deductions, you’re given the choice of either investigating the studios roof, where the deviants escaped, or interrogating the androids confined in a nearby breakroom, to deduce which, if any of them, acted as a mole to let the deviants in.

While the roof option will net a confrontation with a wounded deviant, it’s the interrogation that makes matters interesting.

Not One of Us

Choose the correct series of prompts and questions, and you will begin to see which of the identical androids is deviant. When you’re about to confront the culprit however, the guilty party, rather than attempt to negotiate or communicate with someone who is, in their eyes, enslaved, proceeds instead to completely and literally rip your mechanical heart out.

To reiterate: this android is involved in a scheme to get the message of the deviant’s rising sentience out into the world, and his first inclination is to mortally wound a person who, by all rights, should warrant his sympathy and walk away like nothing happened.

Regardless of Connor’s pre-programmed mission to hunt down deviants, the fact that he is still constrained by his programming should – by the rhetoric of the game – grant him innocence for his perceived crimes prior to deviation. But he’s not – he remains persecuted by those who should be trying to free him. His own status as a victim, as a slave, means nothing.

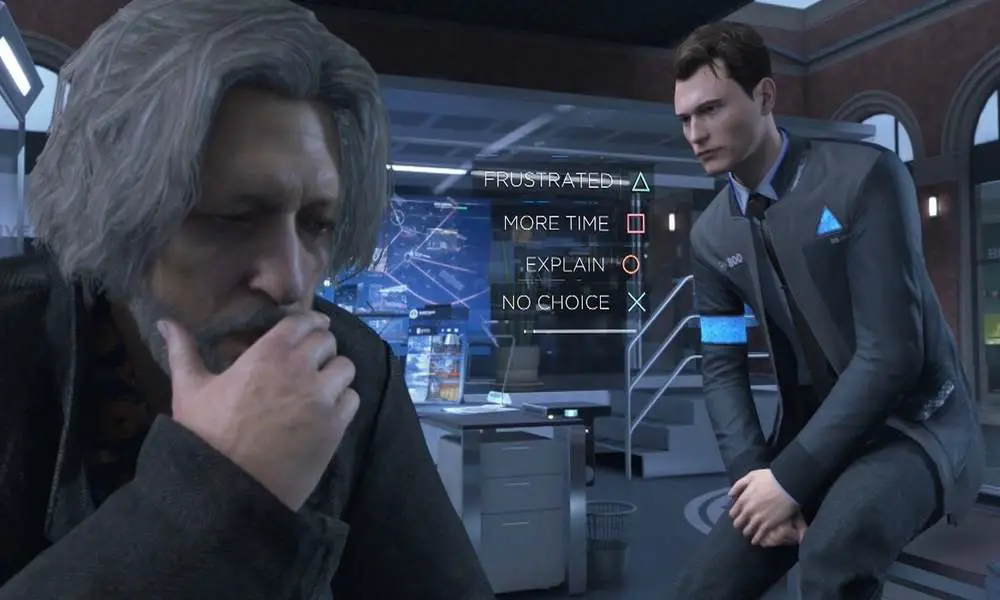

And what do you suppose happens when he finally does complete his mission and has finally managed to track down the deviant organization Jericho, and confronts their leader, Markus? Having gone two-thirds of the way through the game, you are finally presented with the opportunity to make Connor embrace deviancy and shatter his programming. But here’s the kicker: it’s the only chance Connor gets.

If Connor does not embrace deviancy – freedom – when Marcus presents it to him, he will never be given the option again. It doesn’t matter if the player has invested in getting Connor’s android-hating partner Hank to soften his stance. It doesn’t matter if you get Connor to love dogs and rock music. It doesn’t matter if you’ve spared a couple of android sexbots, in love and on the run, from death and dissection.

None of Connor’s choices – to choose the “human” option, to display empathy and kindness and wit – matter, because in the end, despite the core of the game revolving around discovering one’s autonomy, Connor remains the only character who needs permission to become human. His status as a pariah on both fronts renders him incapable of achieving that status through his own merits: he’s too android to be a respected member of the police force, and he’s too police to be included or considered oppressed by the other androids.

This is especially jarring when you consider that you have the opportunity to play Markus less in the style of Martin Luther King Jr. and more in the image of Maximilien Robespierre. Connor can disagree with the steps Markus takes, but his own freedom is still dependent upon Markus more or less granting him permission to escape his programming.

There Are Many Strings On Me

Now let’s say you do become deviant due to the power of Markus’ words. Well, after Connor helps Jericho flee a massive FBI raid, his life is still forfeit because Markus can still choose to murder you for leading the police to the deviant’s safe haven. Despite, remember, Connor being locked by his code and therefore having no autonomy prior. Regardless of his innocence, Connor can still be persecuted by his people – exiled and left adrift at best, executed at worst. Even to the one character whose primary motivation is the protection of android-kind, Connor is disposable.

This narrative renders Connor and anyone in his position as incapable of being integrated into either the main dominating society, as an un/willing oppressor or as a member of the oppressed society. Both view him as a member of the other order, and so he becomes part of neither.

In the most successful route of the game, in which you’ve kept all the major players alive, you’ve warmed the heart of the nation, and prevented a complete robot genocide, Connor is allowed to stand beside Markus on a makeshift stage as the civil rights leader gives a victory speech to his followers.

In the middle of this, Connor is forcibly transported to his mind space. We see him dip in and out of this place throughout the game: a tranquil and yet clinical garden space where the Deviant Hunter presents progress reports to his Cyberlife handler, Amanda. Amanda resides in Connor code as a micro-AI in herself, constantly watching her charge’s actions and “advising” Connor on the best course of action.

But in this moment, the tranquility is shattered. If Connor deviates, the relationship bar with Amanda plummets, the game proclaiming that you’ve betrayed her. It isn’t until this moment that we see just what this means and just how horrifying Amanda’s role truly is.

Where there was once a garden, there is now a raging blizzard. Amanda stands unbothered by the chill, and in a voice as cold as the raging snows proclaims Connor a fool and a traitor. She declares him an unknowing weapon; an android designed to eventually become deviant, gain access to the deviant inner circle and destroy them from the inside. Even in his freedom, Connor is still dehumanized – a robotic Manchurian Candidate, wound up like a toy soldier and let loose.

The scene becomes a tense race. The player must navigate Connor through the howling winds towards an innocuous glowing handprint scanner. This device is seen throughout the game and even interacted with, with no discernible effect or purpose until this moment. The scene flashes back and forth between the player’s attempts to steer Connor towards his salvation and the now Cyberlife guided Connor still standing on stage beside Markus, calmly and subtly pulling out a gun.

Fail to reach the exit point in time, and Markus is murdered on stage, meeting the same grim fate as so many other civil rights activists. Succeed and Connor regains control of his body, shaken but free. But is he really?

Amanda is not destroyed. There’s no evidence that what is within has been purged. The narrative, in not showing us a body, continues with the thread that Amanda, effectively the worst part of Connor, has simply been quelled, not killed. Therefore, the message created throughout the game is maintained: Connor is not only not part of the android community, he remains a constant threat, liable to snap and betray at any moment.

And it’s this mindset that follows Connor all the way to the very end of the game. A Judas. A snake in the grass. A metaphorical Trojan Horse.

Art Mimics Life

We see this phenomenon play out in our modern society, especially in the resurgence of civil protests and anti-police movements seen in the last decade. The exposure of police wrongdoings and wrongful, racially-motivated deaths thanks to twentieth century technological advances has not only allowed for a more public airing of existing corruption, but also heavily widened the existing rift and strained the threads of trust between the nation’s protectors and those they are meant to serve.

With such a chasm creating and solidifying a thought process in minority communities that encourages boils down to “us versus them” it in turn makes it difficult to reconcile when members of the community choose to pursue those professions. In the eyes of some, those community members have turned their backs on “their” people. They, like Connor, have become traitors, and as such are no longer quite as welcome or deserving of the comradery racial injustice can form amongst a community.

And as Connor serves as a metaphor for minority (and especially Black) police officers, this holds true for them. It’s a narrative reinforcement on reality that those who choose a career in law and order, no matter their intentions, are essentially turning their backs and/or being exiled from their people.

By becoming part of an oppressive system, Detroit tells us that those individuals forfeit their right to belong, regardless of their own mistreatment. It tells us that they are tainted, and will never again truly belong; not to their racially impacted civil fraternity nor their community.

Now Detroit is by no means the only game, or even the only medium by which this negative narrative is told. It does bring up a consistently troubling situation in media where, for simplicity’s sake, it is easier to condemn a person in a corrupt institution than the institution itself. And as art mirrors life and vice versa, it becomes easier to condemn a person attempting to influence a corrupted institution through presence than condemn the society that requires someone to have to try to influence or redeem that institution in the first place.

It’s a tactic that is nefarious in its ability to consistently, historically work. And in these last years, when we’re seeing a massive resurgence of civil protests, it becomes ever more important to remember the difference. You don’t fight a disease through what it afflicts; you fight it at the root. Connor’s story serves as a reminder that oppression comes in several forms, and those who fight against discrimination must be careful not to embody its values.

Change doesn’t come or even stick by persecuting or erasing the Connors of the world: it comes about by remembering that they remain themselves victims. Minorities attempting to gain a foothold in an oppressive institution are not to be vilified but guided, assured that they belong in both worlds and encouraged to bridge the gap between their communities and use their influence to destroy that which encourages the continuation of such a racial and societal divide.

Images courtesy of Quantic Dream and Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Have strong thoughts about this piece you need to share? Or maybe there’s something else on your mind you’re wanting to talk about with fellow Fandomentals? Head on over to our Community server to join in the conversation!